When Senator John Glenn climbs into his seat on the Space Shuttle Discovery in late October, four A&S alumni will know exactly how he feels. They've been there.

Richard Gordon was a pilot in the space program's formative years, flying on Gemini 11 in 1966 and Apollo 12 three years later. George "Pinky" Nelson was a mission specialist on three shuttle flights in the 1980s.

This year two A&S alumni have been on shuttle flights, conducting experiments and bringing supplies to Space Station Mir. Michael Anderson made his trip in January (along with UW Engineering alumnus Bonnie Dunbar), and Janet Kavandi flew in June, both as mission specialists.

Then there's alumnus Stanley Love. He hasn't flown yet, but he'll have his chance soon. He was just selected for NASA's 1998 astronaut candidate class. Another four astronauts hail from other UW units.

A Lifelong Fascination

Anderson ('81, B.S., physics) knew he wanted to be space bound from an early age. After receiving his first toy airplane at age three, he was hooked. A few years later, inspired by Star Trek, he regularly took flights in his personal space ship for imaginary trips to the stars. Then, at age nine, he watched the first moon landing and began memorizing the astronauts' names. He was certain that one day his name would be added to the list.

"I can't remember ever thinking that I couldn't do it," recalls Anderson. "I never had any serious doubt about it. It was just a matter of when." His resolve was all the more impressive given that none of his astronaut role models shared his African American heritage.

Kavandi ('90, Ph.D., chemistry) also had a fascination with the night sky and found the stories of the first space flights intriguing. "I thought that would be the best career in the whole world," she recalls, "but when I was young, space flight was a cold war competition between two world powers, and the only astronauts were male military test pilots."

Kavandi says that it was only after the U.S. space program won the "race to the moon" that NASA was able to focus on the more scientific benefits of space travel. When the space shuttle program began hiring women for the first time, shortly after Kavandi graduated from high school, she realized that she might have a shot at being an astronaut.

Dick Gordon ('57, B.S., chemistry) had no astronaut role models while growing up. There was a good reason for this: no one had yet ventured into space. He considered several career options--including the priesthood and dentistry--before becoming a test pilot. Then he watched the historic 1957 launch of Sputnik. He was in space six years later.

"It was an exciting time," he recalls. "NASA was small in those days, with a culture of 'We can do anything.' Space gave us something to look to and hope for."

Like Gordon, Pinky Nelson ('74, '78, M.S., Ph.D, astronomy) did not contemplate becoming an astronaut until he was in his 20s, although he was always fascinated with the sky. "I thought it would be fun, but it wasn't a career goal," he says, "especially since NASA stopped hiring while I was in high school. I was busy being an astronomer." For Nelson, the turning point came when he saw a NASA announcement on a UW bulletin board in 1977. The space agency was once again taking applications. By 1984, Nelson was headed skyward on a seven-day Challenger flight.

The Astronaut's Motto: Be Prepared

Most space flights take about ten days. But preparing for the flight takes more than a year.

First, astronaut candidates complete a grueling training program that includes survival training, high-performance jet training, under-water "spacewalk" training, and space shuttle simulator exercises. They also attend classes on shuttle systems, mathematics, guidance and navigation, orbital dynamics, materials processing, and other subjects. Once assigned to a mission, the training becomes more specific to that flight, covering everything from docking to a contingency space walk.

"The most important objective of any training is to be able to save the crew and the vehicle if something goes wrong," says Kavandi. "Ninety percent of the training is for that type of situation. They pile failure on failure in simulations, so that we will be prepared if an actual failure were to occur in flight." In fact, Kavandi's crew did face a few equipment failures during its rendezvous with Mir. But, she says, "we had trained so many times with no equipment at all that we really didn't have any concerns. It went very smoothly."

Anderson agrees that the simulations prepared him well, but he still recalls his hands sweating as he pushed the button that would dock the space shuttle with the Mir space station. "I'd done it a million times in the simulator, but when it was real--when I was actually docking two quarter-billion-pound vehicles--it was a different moment entirely."

Five, Four, Three, Two, One . . .

After nearly a year of mission-specific training, each of these astronauts was ready and eager for the launch. For some, the moments before liftoff were the most trying. "Once you climb in and get all strapped in, there are still at least two hours before liftoff," explains Anderson. "There are always minor glitches they are working on, and we can hear the discussions of these last-minute problems over the intercom. It's nerve wracking. The last thing the crew wants to do at that point is to climb out of the vehicle. You're focused, you've peaked in your training, and you don't want anything to get in the way of that."

During her launch, Kavandi tried to prepare mentally for a delay. "I had been told by other astronauts not to assume you were going anywhere until the solid rocket boosters ignited," she says, "so as the countdown was proceeding, I was almost expecting a hold or an abort. When the main engines ignited six seconds before liftoff, I was thinking, `Hey, this might just happen!' Then the solid rocket boosters went and shot us off the pad. I just started laughing and crying all at the same time. It was a very special moment."

Perhaps the person with the most trying liftoffs was Nelson. His second flight was scrubbed five times during countdown before it finally lifted off. "Once the clock stopped at twelve seconds," he recalls. "That gets pretty scary. It's a dangerous vehicle to be in at that moment, when a lot of powerful systems are already up and running."

Nelson's third and last flight was emotional for other reasons: it was the first flight after the Challenger accident. "We always knew and still know that every shuttle flight is dangerous," says Nelson. "The Challenger accident just made that more real."

The View of a Lifetime

It's hard for those of us on terra firma to imagine the physical and emotional transformation that takes place when an astronaut is launched into space. Nelson describes the view out the window as "the one transforming experience for every astronaut. It stays with you forever."

Gordon still remembers the view vividly three decades after his first flight. "Looking at Earth from lunar distance, it is awesome to see this delicate planet out there floating in the darkness, a bit like a Christmas tree ornament suspended in the blank void of space," he says. "It makes you think about the fragility of the planet."

Kavandi adds, "My most special memory is seeing the Earth at night, reflecting the light of the full moon off the oceans and clouds, and watching lightning dance around. It was incredibly beautiful."

For those who have no chance of catching that view, Kavandi offers some solace: "When I first looked out the window, I was actually shocked at how well the IMAX films capture what the Earth looks like," she admits. "They do a very good job of almost taking you there."

Pressed to describe his most memorable moment in space, Anderson gets more specific about the experience. "It's probably the moment that we hit orbit," he says. "It is an eight-and-a-half-minute ride to get there. Right before the engines cut off you are being pushed back in the seat by 3Gs of pressure. Then you suddenly go to zero Gs [zero gravity]. I remember being thrown forward in my seat and then watching everything around me start to float, including ice crystals that had formed outside the vehicle. As the sun caught those ice crystals--thousands of them--they looked like brilliant shining diamonds floating in the darkness of space. But that's just one of hundreds of moments that stick out in my mind."

Nelson and Gordon also spent time outside their vehicles on space walks. Both can attest to the challenges of maneuvering in zero gravity in a bulky space suit. "When I did it, we were still just trying to learn how to operate in that environment," explains Gordon. "We were floundering around--literally--trying to understand the basic physics of zero gravity."

By the time Nelson flew, space walks were planned only for specific tasks. His was to tow an ailing satellite, launched four years earlier, back to the orbiter's cargo bay. "That's one experience I haven't been able to put into words yet," Nelson says of his ten-minute, 200-foot journey between Challenger and the satellite. "One of the things I trained to do was to fly the maneuvering unit over to the satellite and stop--not stop flying, but take time and relax and just take it in for a minute or so."

The Russian Connection

Anderson and Kavandi have not experienced the thrill of a space walk, but they have shared a different sort of adventure: a visit to space station Mir. Kavandi spent four days on Mir, conducting radiation experiments while other astronauts transferred materials to and from the space station. "I was truly impressed to see Mir," she says. "It was amazing to realize how long it has been operating up there--over 12 years--and that the Russians have had a continuous human presence there for that period of time. I personally thought it looked to be in pretty good shape for its age."

Anderson also believes that the Russian space station gets a bad rap. "It is functional and very capable of doing its job," he says. "It's still a viable piece of space hardware. The Russians certainly know what they are doing. They fix the problems and continue."

In fact Anderson, whose shuttle crew included a Russian air force pilot, says that "working with the Russians was one of the highlights of the whole deal" for him. "We do things differently and that's a challenge, but a welcome challenge," he explains. "We can learn a lot from each other. It's kind of ironic that we have to leave the planet to get along and work together."

Even more ironic, perhaps, is that our space program was founded on our not-so-friendly competition with the Soviet Union. Gordon says that when he flew in the late 60s, "we were in large part motivated by our competition with the Russians. We were in a cold war, and we were going to beat them."

Launching Down-to-Earth Careers After Space Flight

Since leaving NASA, Gordon and Nelson have watched with interest as the space program has evolved. Although both are thrilled to have explored space, they have gone on to tackle more earthbound challenges.

Gordon served as executive vice-president of the New Orleans Saints Football Club, then focused on industry, where he has worked for--and headed--several firms providing chemical and engineering services. He also has served as technical adviser for portions of a CBS mini-series on the space program and consulted with a Japanese group developing a theme park focusing on space. Now semi-retired, he continues with consulting work in systems engineering.

To the University's delight, Nelson headed back to academia after leaving the space program. He spent eight years as a UW associate professor of astronomy and associate vice provost for research, responsible for moving University-developed technology from the laboratory to the marketplace. In 1996, he left the UW to head Project 2061 at the American Association for the Advancement of Science. The project, says Nelson, "aims to radically reform the educational system so that all students graduate from high school literate in science, mathematics, and technology."

Do these former astronauts ever long for "the old days," when they were in the space program? Both insist they do not. "I miss flying jet airplanes--that was a kick," says Nelson. "But the endless meetings and training kind of lost its charm. I love what I'm doing right now. This is the most challenging job I've ever had." Adds Gordon, "I had my turn and enjoyed every minute of it. End of chapter. Those days are gone forever. I'm not trying to be John Glenn."

As for Anderson and Kavandi, they must "head to the back of the line" and wait their turn to be assigned to another mission, which should happen within three years. In the meantime each is working on some aspect of the international space station, which will be launched, in pieces, beginning next year.

Maybe by the time Anderson's and Kavandi's next flights launch, their children--each has two under the age of seven--will be enthralled by having an astronaut parent. Right now the youngsters are not particularly impressed.

"When my four-year-old daughter came back from the launch, her teacher was very excited and wanted her to tell the class about it," recalls Anderson with a chuckle. "So she stood up and, with great excitement, told everyone all about her trip to Disney World after the launch."

More Stories

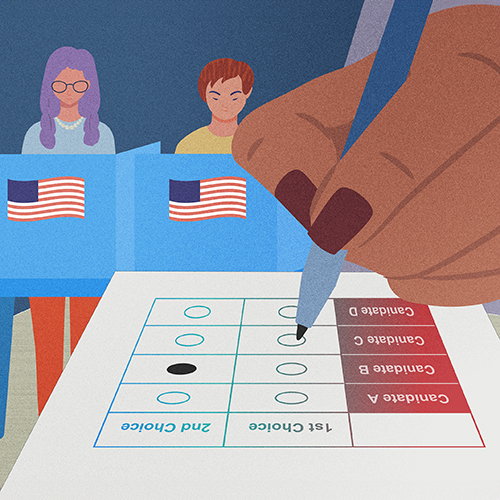

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

A Statistician Weighs in on AI

Statistics professor Zaid Harchaoui, working at the intersection of statistics and computing, explores what AI models do well, where they fall short, and why.

The Mystery of Sugar — in Cellular Processes

Nick Riley's chemistry research aims to understand cellular processes involving sugars, which could one day lead to advances in treating a range of diseases.