When the crew of the space shuttle Columbia perished on February 1, the loss was personal for many in the College of Arts and Sciences. Michael Anderson, payload commander, graduated from the UW with a B.S. in physics and astronomy in 1981.

Anderson knew from an early age that he would become an astronaut. Interviewed for College of Arts & Sciences newsletter Perspectives in 1998, he described his fascination with space.

“It was just the adventure of it,” he said. “As a kid, I spent a lot of time watching science fiction TV shows—Lost in Space, Star Trek—and then I followed the real space program. It seemed like the ultimate thing to do.”

After watching the first moon landing, Anderson began memorizing the astronauts’ names. He was certain that one day his name would be added to the list.

“I can’t remember ever thinking I couldn’t do it,” he said. “I never had any serious doubt about it. It was just a matter of when.” His resolve was all the more impressive given that none of his astronaut role models shared his African American heritage.

At the UW, Anderson planned on majoring in engineering, but the physics courses he took as an elective fascinated him and he decided to switch majors. “Physics was much more of an art, more elegant,” he explained. “It taught me to think like a scientist. I found it more suited to my interests.” He later earned an M.S. in physics from Creighton University.

Anderson’s first space flight was on the space shuttle Endeavor in 1998, which docked at the Mir space station. Among Anderson’s duties was the actual docking of the spacecraft. “I had done it a million times in the simulator, but when it was real—when I was actually docking two quarter-billion-pound vehicles—it was a different moment entirely,” he recalled.

One of Anderson’s favorite memories from the 1998 flight was the moment when the shuttle hit orbit. “Right before the engines cut off you are being pushed back in the seat by 3Gs of pressure,” he said. “Then you suddenly go to zero Gs [zero gravity]. I remember being thrown forward in my seat and then watching everything around me start to float, including ice crystals that had formed outside the vehicle. As the sun caught those ice crystals—thousands of them—they looked like brilliant shining diamonds floating in the darkness of space. But that’s just one of hundreds of moments that stick out in my mind.”

Asked how he handled fear on such a dangerous mission, Anderson said it was “never an issue.” His comments seem particularly poignant today.

“I don’t know why I didn’t experience fear,” he said. “Maybe it’s because the training simply prepares you for it. By the time we make it to the actual space flight, fear has been dealt with—which is good, since you have a lot to do. You’re so excited. You just want to do your job. Fear is one of those things you simply do not dwell upon.”

More Stories

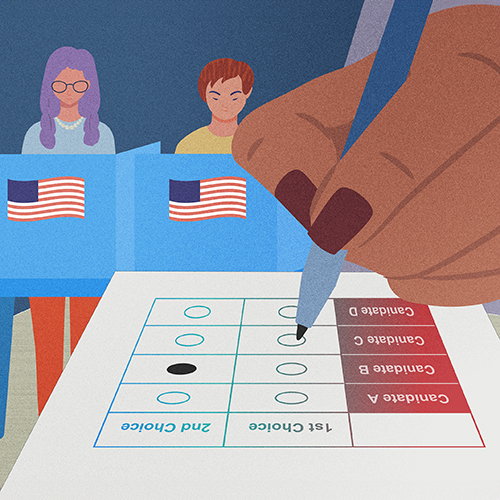

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

A Statistician Weighs in on AI

Statistics professor Zaid Harchaoui, working at the intersection of statistics and computing, explores what AI models do well, where they fall short, and why.

The Mystery of Sugar — in Cellular Processes

Nick Riley's chemistry research aims to understand cellular processes involving sugars, which could one day lead to advances in treating a range of diseases.