The buildings are ivy-covered and cherry trees still grace the quad. But those who think nothing changes at the University of Washington should take another look. In the past few years, the College of Arts and Sciences has embraced change, encouraging long- standing departments to join together to create new, more effective units.

“Tradition is very important in the College,” says David Hodge, dean of Arts and Sciences, “but we need to be open to change as well. Society is changing

rapidly, and our structural reorganization reflects that.”

Joining Forces

Since 2000, four new departments have been created. First geophysics and geological sciences joined together as Earth and Space Sciences. Next genetics joined with molecular biotechnology, a non- A&S unit, to become the Department of Genome Sciences in the UW School of Medicine. Then communications and speech communication became the Department of Communication. Most recently botany, zoology, and biology officially joined as the Department of Biology.

“It’s not about just merging departments,” says Hodge. “It’s about creating something new. It’s very exciting. But it still takes a fair amount of raw courage from all involved.”

And good timing. In each case, recent developments in the discipline or department led faculty to consider changes they might otherwise have rejected.

Consider the case of geophysics and geological sciences. Until recently, the two units had very little common ground. While geologists focused on the earth’s crust, geophysicists worked on a broader scale, looking at problems that extended from the center of the earth to the edge of the solar system. And while geological sciences offered many undergraduate courses, including lecture courses attracting hundreds of students, geophysics was a graduate program with no undergraduate offerings. Several things changed in the 1990s. With technological advances, many tools of geophysics provided higher resolution than before, leading geophysicists to

begin working in a scale more similar to geologists. And the Geophysics Program began offering a handful of undergradu ate courses.

“There was an increasing recognition that there was more overlap and more opportunities to work together in a way that wasn’t possible in the past,” says Michael Brown, chair of the Department

of Earth and Space Sciences. “We began to see that the two departments would be in a stronger position together than apart.”

A similar realization led faculty in communications and speech communication to consider joining forces. Both departments had been targeted for major cuts in the mid-1990s. In the process, the School of Communications had lost most of its professional programs—advertising, public relations, broadcasting—and replaced them with a more academically focused media studies program.

“That change in focus gave the School an opportunity to consider collaborating with speech communication,” says Jerry Baldasty, chair of the new Department of Communication. The two departments began offering courses jointly and sharing computer and media equipment. Before long, “both depart ments saw an opportunity to broaden and strengthen what we were already doing by creating one larger, more comprehensive academic unit,” says Gerry Philipsen, professor of communication and former chair of speech communication.

When genetics and molecular biotechnology (MBT) began discussing a merger, they had less overlap. “We were two departments doing biology research, but we had a very different focus,” says Stan Fields, former acting chair of the new Department of Genome Sciences. “The focus in genetics was on model organism genetics—studying bacteria, yeast, flies, worms, and mice. MBT’s focus was on the development of new technologies.” But the two departments had symbiotic needs. Genetics had a strong and stable faculty but lacked space and resources. MBT had cutting-edge facilities, but had lost several key faculty. “We also recognized that the science is evolving rapidly,” adds Breck Byers, professor of genome sciences and former chair of genetics. “We were aware that our students would benefit from exposure to MBT’s new intellectual approaches.”

The most recent merger involved three units–biology, botany, and zoology—whose differences had become less significant. Zoology focused on animals while botany focused on plants, with the Biology Program recruiting faculty from both to teach interdisciplinary undergraduate courses. But “at the cellular and molecular level, a lot of studies don’t distinguish between plants and animals,” says John Wingfield, professor of biology and former chair of zoology. “And in studying ecology, it is a detriment for those areas to be separate.” Like other departments before them, they realized “it was time to consider joining together.”

Putting it to a Vote

The idea of creating a new department is one thing. Making that happen is quite another. First, the faculty must support the plan—no small challenge when dealing with dozens of individuals, each wondering how the change will impact his or her work.

“Creating a new department was a pretty scary proposition,” recalls Barbara Warnick, professor of communication and former chair of speech communication. “There was a high level of trust required—in the process and in the administration’s promises to be supportive.”

The faculty vote to approve the Department of Earth and Space Sciences came quickly, after just one meeting of geological sciences and geophysics faculty. “There was this sense that we

didn’t want to lose momentum,” says Darrel Cowan, professor of earth and space sciences and former chair of geological sciences. Even with the short timeline, the vote was nearly unanimous.

“I credit the faculty and graduate students—who were also at the meeting—with really getting behind the plan and not throwing lots of roadblocks,” says Cowan.

Other departments took it slower. The idea of a Biology Department was raised at a zoology retreat but not put to a vote for another year. “We deliberately did not have a vote that day,” recalls Tom Daniel, chair of the new Department of Biology. “We invited Joe [Ammirati, chair of the Botany Department] to share his perspective and asked people to discuss advantages and disadvantages of creating a new department. People came into the meeting cautious, thinking ‘What’s going to happen to the world?’ and came out surprised that they enjoyed the process and outcome.”

When finally put to a vote, the Biology Department was approved by a vote of 50-1, with one abstention. Votes for a Department of Communication and Department of Genome Sciences were similarly positive.

A New Culture with New Challenges

Even with nearly unanimous support, creating a new department is a challenge. There are endless decisions to be made about curriculum and organizational structure. The A&S Dean’s Office has helped departments tackle these chal lenges by providing programmatic and financial support.

“The level of support from the Dean was really impressive,” says Baldasty. “I don’t think we could have done it without that support. A key ingredient to our success is that the College met its promises to us—and exceeded them.”

For the creation of the Department of Genome Sciences, the College helped in a different way: by letting go. “It came down to resources,” says Fields. “We knew that recruiting faculty and renovating facilities would require millions of dollars. Arts and Sciences had less discretionary funding than the medical school and David Hodge recognized this. He altruistically felt that if this was the best thing for the Genetics Department, he would be willing to let it leave the College and move to the School of Medicine. I felt that he had the University’s best interest at heart.”

For each new department, there are still details to be resolved, including intangibles like the creation of a department “culture.”

“When departments come into this, they come with different sets of alumni, different identities, different histories, different professional alliances, different buildings, different staff,” says Philipsen. “The challenge is to create a new culture for the department that reflects its unique strengths.”

“This is a real opportunity for those involved,” adds Barbara Wakimoto, professor of biology and former director of the Biology Program. “It’s a chance to re-examine how we do things and figure out what will work best. We’re excited to see it all finally come together.”

More Stories

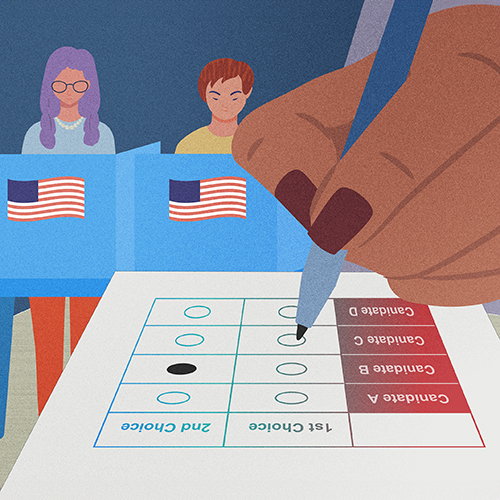

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

A Statistician Weighs in on AI

Statistics professor Zaid Harchaoui, working at the intersection of statistics and computing, explores what AI models do well, where they fall short, and why.

The Mystery of Sugar — in Cellular Processes

Nick Riley's chemistry research aims to understand cellular processes involving sugars, which could one day lead to advances in treating a range of diseases.