On November 9th, as UW senior Lucas Braden drifted off to sleep, his mind was reeling from all he’d seen and heard that day. He was staying in a refugee camp in southern Ghana, where he had spent the weekend talking with Liberian refugees. The next day he would return to Kumasi, home to the UW’s program in Ghana, and share his experiences with classmates.

The refugee camp visit was one of many memorable moments for Braden, one of twelve students participating in the UW’s new Ghana program, offered by the Jackson School’s Program in International Studies and the Program on Africa in conjunction with the School of Music’s Ethnomusicology Program. Students in the program spent four months at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), taking classes from Ghanaian faculty with African classmates as well as courses taught by KNUST and UW faculty for UW students.

“We envisioned a combination of classes,” says Linda Iltis, lecturer in comparative religion and South Asian studies and academic counselor in the Jackson School of International Studies, who led the Ghana program with her husband Ter Ellingson, professor of ethnomusicology. “We felt it was important to have the students be in classes with Ghanaian students, but we also wanted to provide a thematic focus.”

Iltis and Ellingson credit Daniel “Koo Nimo” Amponsah, a Ghanaian musician and visiting artist at the UW in the late 1990s, with providing the “seed” for the Ghana program. After teaching at the UW, Koo Nimo arranged for the couple to visit KNUST in Ghana for preliminary discussions about starting a UW program there. They made the trip and “fell in love with the country,” says Iltis. A year later the University of Washington formalized its affiliation with KNUST, and the program was born.

Iltis and Ellingson planned to teach separate courses in Ghana—hers focusing on religion and identity, his on urban anthropology—but found so much overlap that they decided to combine their classes. They took full advantage of their African setting, inviting frequent guest speakers from the local university and community and planning nearly two dozen field trips, ranging from a brief visit to a local market to day-long traditional court sessions and funerals to a three-day journey to a xylophone festival, a chief’s palace, and a hippopotamus sanctuary. They met Ghanaians from every walk of life, including fishermen, businesswomen, and political and religious leaders. “There is so much that’s interesting there,” says Iltis, “that it was hard to limit ourselves.”

For Braden, the field trips were a highlight of the program. “The experience of being there, visiting all those sites, gave us a perspective that books could never portray,” he says. His favorite? A trip to Cape Coast, which included an excursion to a rain forest with stunning canopy bridges and a visit to two historic slave castles with cells to hold slaves being sent across the Atlantic as part of the slave trade. “It was impacting to see those cells, feel what happened there,” says Braden.

The class also visited many shrines and attended “akoms,” or possession ceremonies, in which the priest is possessed by various deities through which he interacts with the supreme deity. “It’s like a communion,” explains Ellingson. “The spirit possession is kind of an ecstatic experience.”

These and other celebrations often involve dancing, and the students were always willing to participate. “We told the students early on, ‘You never turn down an invitation to dance,’” says Ellingson. “People are not interested in how good a dancer you are, but rather what kind of human being you are. Ghanaians have a strong memory of white people in colonial days looking down on ‘the natives’ dancing. So it’s important to take part in the dancing.”

The students also did their fair share of drumming. As a group, they took a weekly Ghanaian drumming and dancing class. Miki Sugahara, a sophomore majoring in music and international studies, took extra lessons each weekend and volunteered at a drum store in town, hoping to learn how to make a drum. “I went about once a week,” she says. “I just helped them carve, sand…whatever they needed. In the end, I made my own drum with their help, using a tree from the village where one of the staff grew up.”

Volunteering at the drum shop, Sugahara learned about more than drums. “Working with people in the town, I learned a lot about the culture,” she says. She found the people warm and welcoming and discovered that everyone seemed to be related. “It was hard to go home at night,” she says. “When I was ready to leave, I’d spend 30 minutes saying my goodbyes to everybody. Then their cousins, who all lived nearby, would come over to say goodbye,” she recalls with a laugh. “It would take forever.”

Sugahara was not the only UW student to develop ties to the Ghanaian community. Through a research project assigned by Ellingson and Iltis, all of the students engaged with the community at some level. “We wanted to get them out of the classroom in their interaction with Ghanaians,” says Ellingson. “And we wanted them to experience doing research firsthand in a different culture.”

The students could choose almost any topic for their research project, concluding with a final paper. Their topics ran the gamut from Asante proverbs to the role of women in Ghana, a matrilineal society. Two students volunteered with an HIV/AIDS project at a local social welfare agency. Another focused on “Women, Witchcraft, Christianity, and the Law,” traveling to a “witch” village that is home to women accused of witchcraft and banished from their own villages. And then there was Lucas Braden’s research project, which led him to the refugee camp in northern Ghana.

Braden, an international studies and political science major, arrived in Ghana with an interest in civil conflict. In the KNUST dormitory he met John Duwana, a Liberian refugee who shared his experiences growing up in Liberia, fleeing the country, and arriving in a refugee camp in Ghana seven years ago.

“In Liberia he watched his father be tied up, doused with gas, and burned alive,” says Braden. “His brother went for food one day and never returned. All the people in his life were destroyed.” At the refugee camp, Duwana worked as a laborer and finished his education, then spent several more years just marking time. He offered to take Braden to the camp for a weekend.

“There are still 1,500 Liberian refugees living in that camp,” says Braden, who spent his days there talking with people, jotting notes, and taking photos. “It was a very sobering experience. You see people in a position of hopelessness. They spend their time in limbo, with no idea of what the future has in store for them. It really opens your eyes to the world and to how civil conflict destroys lives.”

Returning to Kumasi, Braden described the refugee camp to his fellow UW students, just as they shared their unique experiences with him. That sharing, he says, was the best part of the Ghana program.

“We came with different majors and distinct interests,” he explains. “That created a great dynamic. We each went off to do our own research and then came back and shared our experiences. It helped us all appreciate the complexities of Ghanaian society—how it all comes together to form this complex identity.”

Iltis and Ellingson hope the program will be offered again, and are looking for other UW professors to participate. “The University in Ghana is keen on doing this again, and so are we,” says Iltis. “It really is an amazing opportunity.”

More Stories

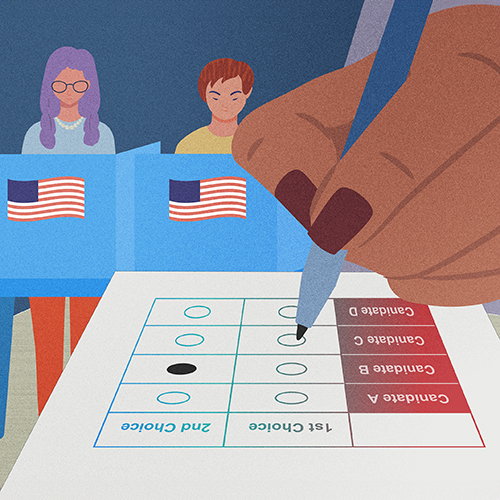

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

Finding Family in Korea Through Language & Plants

Through her love of languages and plants — and some serendipity — UW junior Katie Ruesink connected with a Korean family while studying in Seoul.

Dancing Across Campus

For the dance course "Activating Space," students danced in public spaces across the University of Washington's Seattle campus this spring.