It’s showtime. Charity Ranger takes a deep breath and rolls her wheelchair toward the center of the dance floor, where she and two classmates begin performing carefully rehearsed dance movements. Soon Ranger is perched on the back of another dancer, arms outstretched, and begins rolling over a second dancer onto the floor before returning to her wheelchair.

The performance, attended by an audience of about 50 guests, was the culmination of a new course, “Integrated Dance,” offered by the UW Dance Program during Summer Quarter 2004. The course brought together dancers of varying abilities, including several—like Ranger—who use wheelchairs.

“The focus is on dancing and creating,” says Jürg Koch, Dance Program lecturer, who

taught the course and has danced professionally with CandoCo Dance Company, which specializes in integrated dance. “The course challenges and enables students to explore and develop their individual abilities within dance.”

For Ranger, a senior majoring in communication and diversity and disability studies, the prospect of participating in a dance course was nothing short of terrifying. She agreed to sign up when her close friend Marisa Hackett, a dance minor, promised that she would also take the class.

“Marisa hounded me to take the course,” jokes Ranger. “My adviser did the same. Having Marisa there gave me a sense of security. Being a student with disabilities can create challenges, especially if you’re doing active things. I wanted someone I trusted to be there to back me up if I said, ‘No, I can’t do this.’”

Developing Trust Through Improvisation

Koch designed the course, which met for ten hours each week, to parallel the structure of a dance company’s daily schedule: warm-ups, then dance exercises—including improvisation, and finally rehearsal.

For Ranger and Hackett, the improvisational exercises were a highlight. “For both of us, a favorite was an exercise called ‘leading and following,’” says Ranger. “Students worked in pairs, with one closing her eyes. One person would hold out a hand. The other would then put their hand under it and the first would have to follow their movements. It could involve moving around the room or just moving parts of your body.”

“That exercise was really good for learning how each others’ bodies moved,” adds Hackett. “We did it right off the bat and it helped people become comfortable with each other.”

Jamie Stults, a dance major, says that becoming comfortable with other dancers is always a process. But there is an added dimension when working with dancers with disabilities, particularly when the movements involve bearing other dancers’ weight or sharing weight. “There was inhibition at first,” she admits. “It was a trial and error process that required communication. People needed to say, ‘I can take more weight,’ or ‘That hurts.’ We all became more confident as time went on.”

Different Abilities, Different Challenges

Many movements that emerged from the improvisation exercises were later incorporated into the dance piece performed at the end of the quarter. Although Hackett had studied dance for years, the freedom to choreograph her own movements was new—and challenging. “I come from a ballet background, where everyone follows basic steps,” she explains. “Here we were expected to do things completely improvisationally, on our own. It gave me a lot of anxiety.”

Ranger had her own concerns. When the class did formal exercises each day—everything from stretching to leg lifts to leaps—she had to find ways to adapt those exercises to fit her abilities. She would move an arm, for example, when the exercise called for lifting a leg.

“This can be a huge challenge for students with disabilities,” says Koch, who has taught integrated dance for more than four years. “In a more homogeneous class, a student can ‘ride’ along with other students, following their lead. But when students must come up with their own alternate movements, they don’t have the same cues. They have to remember each time how the move translates to their body. And to make things more difficult, they are often the students with less dance experience.”

For Ranger, the challenge proved overwhelming. At one point during the first week, she left class in tears. “It just felt so hard,” she recalls. “Jürg was very nice about it. He came out and sat with me, listening and talking for ten minutes.”

The tears abated, but Ranger’s frustration did not. Eventually she and fellow student Julia Trahan expressed their feelings—rather vocally—in class.

“We were indignant that we had to do adaptations of exercises when the able-bodied students didn’t have to,” she recalls. “The whole class ended up having a discus-sion about it, which was really helpful. Jürg explained that no matter what your ability, you’re going to move your own way.”

Having taught integrated dance before, Koch was not surprised by the students’ response. But he knew that tailoring the class exclusively to the two students was not the solution. Nor was offering a class solely for disabled students.

“There’s a lot to be learned in the exchange between dancers with different abilities,” he says. “Particularly when it gets to partnering, it becomes really interesting. It involves different centers of gravity, different holds, different grips. And wheelchairs move and become part of the dance.”

A Final Performance

By the end of the quarter, frustrations abated and all of the students had gained confidence in their abilities and trust in each other. Their final nine-minute performance was testament to how far they’d come in four weeks.

“Performing was a different kind of scary than I’ve experienced before,” says Ranger. “When it was done, there was a real sense of accomplishment. I think about my body differently now.”

Would she sign up for the class again? After a long pause, Ranger says, “Probably.”

“It was a wonderful experience,” she explains. “but it was so far outside my comfort zone. There was crying, there was screaming. Am I a better person for it? Yes. Has it enriched my life? Definitely. I really liked this class. But getting to the point of liking it was very, very scary.”

More Stories

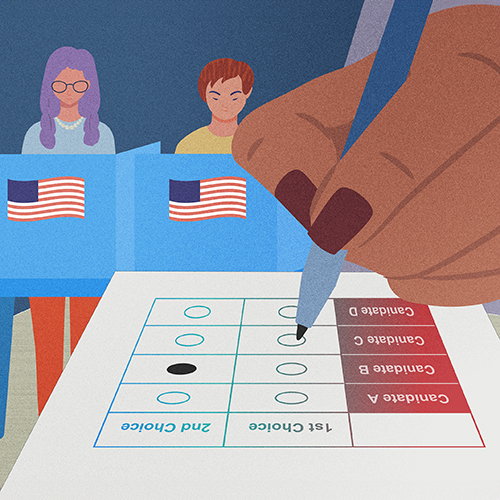

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

Interrupting Privilege Starts with Listening

Personal stories are integral to Interrupting Privilege, a UW program that leans into difficult intergenerational discussions about race and privilege.

Dancing Across Campus

For the dance course "Activating Space," students danced in public spaces across the University of Washington's Seattle campus this spring.