What do migratory birds, public housing, and pea patches have in common? They’re among the topics being explored in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Workshop, a hands-on course through which students tackle real-life questions with a geographic or spatial component.

“Imagine if you married computer mapping software with Excel, allowing you to store or analyze information on a map,” says Sarah Elwood, associate professor of geography. “That’s the idea behind GIS technology.”

Elwood and Tim Nyerges, professor of geography, take turns teaching the GIS Workshop, offered each spring quarter as a capstone experience for geography majors. The course includes weekly lectures and discussions on GIS-related issues, but most notable is the assignment of a quarter-long community project.

Students—a maximum of 40 enroll each quarter—work in small teams, each assigned to a community partner such as Audubon Washington or the Civic Legal Aid Housing Task Force. Research questions run the gamut from analyzing migratory bird routes to assessing a federal housing program’s social impact.

All students in GIS Workshop have taken prior GIS courses. Senior Will Griffith, whose team identified optimal sites for new Pea Patch gardens in Seattle, found his previous GIS coursework essential “not only to know how to accomplish our goals, but in order to determine what goals can or cannot be accomplished with GIS.”

Yet traditional coursework can only go so far. Even the most effective class exercises lack the messiness of real-world projects. “We filter out the unruliness so students can learn what they need to learn, like training wheels on a bike,” says Elwood. “We provide data sets where data are consistent and you know it will work.”

GIS Workshop, in contrast, embraces the messiness of real-world GIS projects. The question posed by the community partner may be “barely articulated” at the start of the quarter. Students may be stymied by inconsistent data. The team may struggle with personality conflicts. Nevertheless, they must provide a finished product by quarter’s end.

“The students gain an understanding of the human side of GIS projects, working with two or three other students and a community partner who may or may not know about GIS,” says Elwood. “They have to figure out what’s feasible, and they have to figure out how to work together.”

Mark Kittinger, whose team worked with the Penny Harvest Youth Philanthropy Project, found the collaboration tremendously satisfying. “Working with an eager and enthusiastic client made the project run more smoothly and led to a better end result,” says Kittinger. “And it made us more enthusiastic.”

Penny Harvest is a project through which K-12 students collect pennies—thousands of them—and donate the funds to community-based agencies of their own choosing. Kittinger and his teammates analyzed patterns in the income levels and demographics of schools participating in the program and where the students chose to donate the funds. “I liked that our efforts are part of a greater cause, as opposed to class assignments that are turned in and forgotten,” says Kittinger. “Our work will have an impact on how the project can grow in the community.”

Even the most successful projects have glitches. During the quarter, teams have several opportunities to share their progress and challenges with classmates during massive brainstorming sessions. “The idea for this came from students,” says Elwood. “They thought it would be cool if they could learn what other groups are doing and help problem solve.”

The teams also seek advice from two graduate student teaching assistants (TAs) assigned to the course. “Each group may need help in a different way,” says Elwood. “The TAs facilitate both the technical and the human side of the project. I couldn’t do this class without their support. With 40 students and 12 community groups, if I were dealing with all of their concerns one-on-one, it would be more of a circus than it already is.”

Just recruiting a dozen community partners is a challenge in itself. The partners must be willing to collaborate with students, and must have a GIS-appropriate project that both fits the course’s ten-week schedule and engages undergraduates. That’s a tall order, which is why Elwood is always in recruiting mode. “I’m a GIS evangelist,” she admits with a laugh. “It’s terrible. At a party, don’t get me started.”

Fortunately, many of the community partners return year after year. Solid Ground, formerly the Fremont Public Association, is the umbrella organization for a number of community groups that have participated in the GIS Workshop. Audubon’s projects are ongoing, with students building on what their predecessors accomplished the previous year.

The payoff for all this hard work? “I have not taken any class in my college career that has more effectively prepared me for life outside of college,” says Griffith, who plans to pursue a career in GIS. He and his classmates will have an advantage as they seek jobs, thanks to their real-world GIS experience. Participating organizations also benefit, receiving valuable GIS analysis at no cost.

And then there are the benefits for faculty teaching the course. Although it’s a daunting task to recruit all those community partners, plan lectures, and oversee a dozen projects, Elwood finds the experience both enlightening and inspiring.

“Our students are amazing,” she says. “Every year, I learn something new from them. It’s such a gift to get to work with them. It makes me optimistic about the world.”

More Stories

Is This Presidential Campaign Different?

UW History professor Margaret O'Mara provides historical context for this moment in US presidential politics.

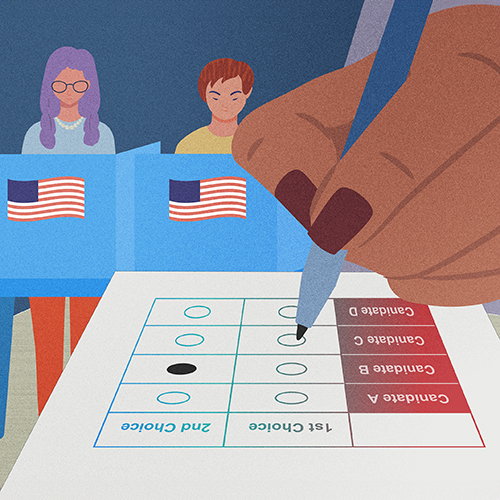

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

Making Sense of This Political Moment

To navigate this momentous election season, Arts & Sciences faculty suggest 10 books about the US political landscape.