Millions of Americans with hearing loss turn to hearing aids for help. They spend thousands of dollars for stateof-the-art devices, anticipating a return to near-normal hearing with use of the aids. So why do nearly half of all hearing aid customers stop wearing their hearing aids?

Kelly Tremblay, professor and interest group head of audiology in the Department of Speech and Hearing Sciences, noticed this trend when she worked as an audiologist in a hospital years ago. “I would put hearing aids in two people, and despite applying all that I knew, the outcome for them could be very different. One would love it; the other couldn’t stand it and would reject it altogether.”

Convinced that the disparate responses had more to do with the patients’ brains than the hearing aids, Tremblay decided to return to school for a PhD in neuroscience. “I wanted to merge brain neuroscience with the clinical problems I saw,” she explains. “No matter how well engineered a hearing aid is, sound still has to go from the ear to the brain. Everything we hear still has to be processed by the brain.”

To learn more about the brain’s role in hearing, Tremblay and graduate students in the Department of Speech and Hearing Sciences use EEG (electroencephalography) technology to study the brain activity of individuals taking specialized hearing tests. Using behavioral measures—asking the listener to do a task, for example—they can determine what the subject is hearing and understanding. A concurrent EEG can show what’s happening in the brain.

What is immediately evident from these tests is that brain response changes with age. While hearing aids tend to be fit the same way regardless of the user’s age, our brains translate sound differently as we grow older. Tremblay and colleagues are exploring whether some individuals’ brains are more sensitive to background noise than others—likely a key factor in their satisfaction with their hearing aid.

“Hearing aids amplify sound, but they also amplify background noise,” says Tremblay. “As those two things overlap in frequency, it can be hard to separate them. I think some people’s brains have huge problems distinguishing between foreground sound and background noise and that the problem becomes worse as we age. How to translate this knowledge into better hearing health care is one of our goals.”

Tremblay’s team also researches the potential of training the brain to more effectively distinguish between different sounds that are important to speech perception. So far, she says, the jury is out on whether such efforts will translate to improved hearing. “My mission is to understand what the training does. Is it just training people to be more attentive listeners? Or is it actually rewiring the brain? I think training can be helpful, but we’re still looking for evidence that it really makes a difference in people’s everyday lives.”

Beyond all the neuroscience research, Tremblay believes that something decidedly more low-tech may also greatly impact hearing aid use: counseling. Helping hearing aid users—and their loved ones—understand the devices’ limitations can go a long way toward acceptance of the admittedly imperfect technology.

Managing expectations can be particularly important for couples who may be disappointed that communication challenges remain despite hearing aid use. At the UW’s Summer Intensive Auditory Rehabilitation Conference, led by Speech and Hearing Sciences assistant professor Jessica Sullivan—and based on a program at Sullivan’s alma mater, the University of Texas at Dallas—students, clinicians, and professionally trained counselors work with adults living with hearing loss and their communication partners who wish to improve their communication skills. The five-day conference includes group classes on coping, facilitating communication, and technological advances.

More Stories

Is This Presidential Campaign Different?

UW History professor Margaret O'Mara provides historical context for this moment in US presidential politics.

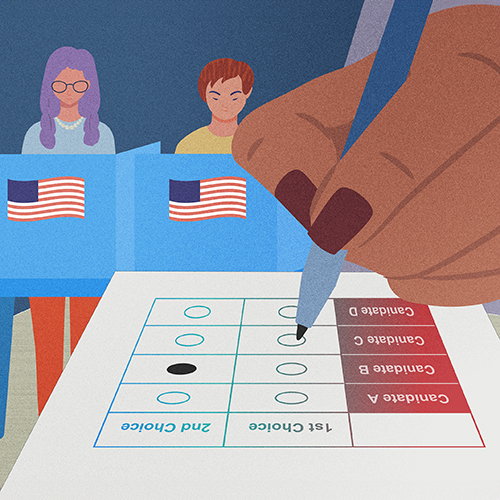

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

Making Sense of This Political Moment

To navigate this momentous election season, Arts & Sciences faculty suggest 10 books about the US political landscape.