Christopher Parker, associate professor of political science and Stuart A. Scheingold Professor of Social Justice, has been studying the Tea Party since 2010 and has written Change They Can’t Believe In: The Tea Party and Reactionary Politics in America, to be published in March 2013. Parker sat down with Perspectives editor Nancy Joseph in early October to share his insights on the Tea Party’s rise to popularity.

How did you become interested in the Tea Party?

In 2010 I put together a survey of seven states, looking at voters’ attitudes. My colleague Matt Barreto suggested that I include a question about the Tea Party, so I included one. After going into the field collecting data, I kind of forgot about that question. But then I saw an article by Juan Williams in the Wall Street Journal in which he said that the Tea Party folks are angry but basically not too different from other conservatives. Days later I read an article in The New York Times by Frank Rich in which he said there’s something very wrong with the Tea Party folks. After reading both pieces, I turned to my dog and said, “This is interesting, Daisy. I happen to have data on this. Let me check this out.”

I started looking at this stuff empirically—looking at the relationship between support for the Tea Party and things like racism, anti-Obama sentiment, homophobia, and xenophobia. The connection was there. And that’s kind of where my interest in the Tea Party began.

Can you share some of your findings?

In the surveys, one thing we did was compare Tea Party conservatives and non-Tea Party conservatives on questions like whether or not you believe Obama is a practicing Christian, or whether or not you believe Obama was born in America. There are like 30 to 50% gaps between Tea Party conservatives and non-Tea Party conservatives. Moreover, if you look at the differences in the two groups when asked if you want Obama’s policies to fail, it’s about a 40% gap. If Tea Party conservatives were just conservatives, we wouldn’t see any difference. But on many issues, we see huge differences, which supports our claim that these are reactionary conservatives, not mainstream moderate conservatives.

The Tea Party’s official platform places most emphasis on fiscal issues, but it sounds like your research has found that not to be the case.

There are some Tea Party supporters who are really about fiscal conservatism, fiscal responsibility, and limited government. There’s no question about that. However, let me just pose this: The deficit increased on Bush’s watch by 104%. He entered the White House with a $700 billion surplus; he left with a $1.3 trillion deficit—a $2 trillion swing. Where was the Tea Party then? You didn’t see this mass movement until we got a black man in the White House. So while a certain segment of Tea Party supporters are about fiscal responsibility and small government, there’s more to it than that. If they were truly about that, we would have seen them come out of the woodwork during Bush’s watch.

members are really just conservatives, then the content should pretty much parallel what we see on the National Review Online. But in the National Review Online, 66% of the content was about big government and national defense. The same issues only constituted about 23% of Tea Party websites’ content. Now if you look at content in the National Review Online related to racism, attacks on Obama, and conspiracy theories, that was about 10% of the content. On Tea Party sites, it was about 40% of the content. Granted, the National Review Online has these conservative intellectuals writing for them while the Tea Party websites have citizen activists writing for them, but it’s still a really good proxy for the ideological leanings of the Tea Party. It’s not like it is 180 degrees out, but they’re not even close.

Is there historical precedence for this sort of conservative movement gaining traction quickly?

We have seen movements like this before, when reactionary conservatives didn’t want change at all. We saw it with the anti-immigrant Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s, with the Klan of the 1920s, and with the John Birch Society of the 1950s and 60s. The Tea Party is the present iteration of all these conservative reactionary movements. This is nothing new.

People may be disturbed that you lump the Tea Party together with the Ku Klux Klan.

I know that some people will be alarmed that we put the Klan and the Tea Party in the same boat, but we think it would be intellectually dishonest not to do so. What motivates more mainstream conservatives—small government, law and order—is about the place of government in American society being minimal. If you look at Robert Taft, who was the standard bearer for the conservatives from the 1930s to his death in the 1950s, he believed in a social safety net even if he felt the New Deal went too far. Eisenhower, same thing. They realized that sometimes people need a hand and sometimes change is necessary to avoid something more revolutionary happening. The people in the Tea Party, they don’t believe in that.

...while a certain segment of Tea Party supporters are about fiscal responsibility and small government, there's more to it than that. If they were truly about that, we would have seen them come out of the woodwork during Bush's watch.

Tea Party supporters believe that their country is being stolen from them. With the Know-Nothing Party in the 1850s, it was the immigration of Catholics from Ireland and then Italy. The Klan of the 1920s, it was the return of the new Negro following World War I, the burgeoning of the women’s rights movement…they felt like everyone was forgetting their place in the American social structure. Same thing with the John Birch Society. They felt that their country was being stolen from them through this alliance between Eastern elites, the civil rights movement, and communists. The same thing right now. What sort of slogan do all these movements have in common? “We’re real Americans. We’re patriotic.” In actuality, that couldn’t be further from the truth. Any time you have somebody running around talking about how they are real Americans or real patriots, you should be suspicious because they are anything but.

Then how has the Tea Party gained so much influence, particularly within the Republican Party?

Obama’s presidency mobilized them. Having a non-white man in the White House, they felt, “We’re losing our grip on our country.” As for their influence on the Republican Party, regardless of what [one] may think of their politics…they are active, they are vocal, they are knowledgeable. Politicians have to listen to that, because these are the people who are going to be going out and voting for them. These are the people who are going to be mobilizing against them if they don’t represent their interests. That’s a major reason why we see the Republican Party moving further and further to the right—because as we show empirically, controlling for myriad factors, people who strongly support the Tea Party are much more likely than people who don’t to have voted in the 2010 election, to have attended political meetings—all these things that politicians look for. They are active, they are vocal, they are spending money, they are doing things that politicians must pay attention to. That’s why it played out in 2010 the way in which it played out. If you look at people that are in the House who have any sort of tie to any Tea Party—that can be anything ranging from them being a member of a Tea Party caucus to having spoken at a Tea Party event—85 members of the House were in some way affiliated with the Tea Party, plus 8 to 10 senators. Enormous influence. Enormous influence.

Can you give an example of how that influence has changed the environment in Congress?

When you look at John Boehner, Speaker of the House, he’s a typical country-club, more moderate conservative. But now, with a Tea Party faction in the House Republican conference, he can’t afford to broker any compromises because he has House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, who caters to the Tea Party, breathing down his neck. Cantor is threatening to Boehner because if the Republican caucus perceives Boehner as compromising too much, they may replace him with Cantor as Speaker of the House. Think about the grand bargain that Boehner and the President were trying to strike. Well, they couldn’t do it because Boehner was continuing to be pulled to the right by the Tea Party. So the Tea Party caucus and influence is all throughout the House, and to a lesser degree in the Senate.

What’s been the Tea Party’s focus during the current election season?

This time around, they’re not as visible as they were in 2010, but that’s only because they are working at the state and local level so that they can build a more sustainable infrastructure.

Given the history of similar groups in the past, how do you see this movement playing out over the next decade?

There is a book by Theda Skocpol and Vanessa Williamson, The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism, in which they show, among many findings, that people who are still living who were part of the John Birch Society are now Tea Party members. So I would say that, as long as Obama is in the White House, they are going to be around. Beyond that, once he leaves the stage, I think they’ll go away. But as soon as we get someone else in the White House who is not a white male—it could be a Latino, it could be a woman, it’s going to be the same thing.

I anticipate you will have a lot of backlash when your book comes out.

I already had backlash in 2010, when the data first came out. I used to get crazy emails, phone calls, and letters from people who would ask, “Who are you? Why are you saying these things? That’s not who we are.” So this won’t be my first rodeo.

More Stories

Is This Presidential Campaign Different?

UW History professor Margaret O'Mara provides historical context for this moment in US presidential politics.

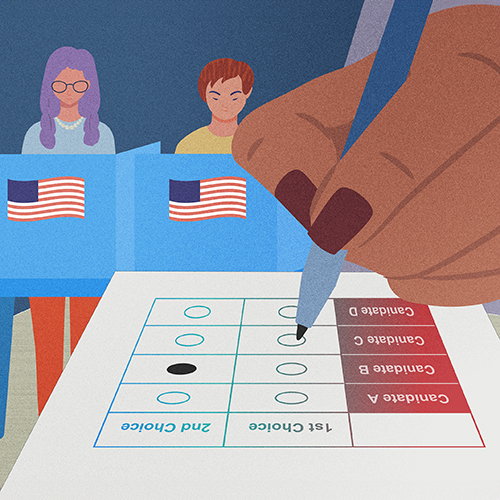

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

Making Sense of This Political Moment

To navigate this momentous election season, Arts & Sciences faculty suggest 10 books about the US political landscape.