Joel Migdal knows that the Middle East conflict—and the United States' role in it—can be confusing, with more characters and subplots than an epic novel. He hopes his new book, Shifting Sands: The United States in the Middle East, can shed some light on the ongoing conflict and U.S. involvement over the past half century.

Migdal, professor of international studies and Robert F. Philip Professor, has been writing about the Middle East and state-society relations worldwide for more than forty years. He answered a few questions about his book for UW Today earlier this year, and provided a few additional thoughts last week in response to recent events.

What is the concept behind this book?

The Middle East is on the front page almost every day with stories of the latest crisis. Shifting Sands provides a broader understanding of the region—a way to make sense of daily events and of the United States as a player in the region.

You write that “For more than half a century following World War II, Washington applied a fixed strategy to a moving target”—hence the “shifting sands” of the title. Why was this true, and what has been its effect?

As a global power after World War II, the United States needed a broad strategy for being involved in so many regions, many for the first time. The Cold War became the framework with which U.S. leaders began to think about these unfamiliar areas, pushing them to find some way to be involved in all corners of the world without bankrupting the country. The result was policies that tended to underplay the important differences from region to region.

How did the George W. Bush administration differ from those before it in viewing the Middle East and responding to its crises? And how does the Obama administration compare to those before it?

There were two radical turns in U.S. foreign policy. The first was by FDR and Truman, in which they made the United States into a global power. The second was by George W. Bush, in which he discarded key limitations that had been built into U.S. foreign policy, including sharing the burdens of being a player in every corner of the world with regional allies.

The Obama administration has sought to return to some of the pre-Bush tenets, but that has been difficult both because of the economic crisis he inherited and because a return to old policies looks now like a retreat.

There certainly are limitations on what the United States can accomplish in the region, especially in as volatile a period as the one it is experiencing now. Still, the U.S. is a formidable player in the Middle East even today.

You write that you believe the United States can do more in the Mideast than merely, as one critic said, “keep disorder at bay” despite the “abject failures” of its policies in recent years. Briefly, how can the U.S. encourage peace and democracy in the region?

There certainly are limitations on what the United States can accomplish in the region, especially in as volatile a period as the one it is experiencing now. Still, the U.S. is a formidable player in the Middle East even today. It must use its leverage in three ways: serving as an active mediator in regional disputes; engaging in direct negotiations with its own antagonists, like Iran; and working to build new regional alliances.

What changes have you seen in the Middle East since your book was published earlier this year?

The most interesting and distressing thing that has happened is the advanced disintegration of states in the region. Syria was already in a state of semi-disintegration and that has proceeded. Iraq wasn’t, but now it looks like it is falling apart. Libya has begun to disintegrate badly. There are difficulties in Yemen and Egypt, and Turkey is undergoing a severe crisis. What is happening in Iran is unclear. So for the United States to figure out what’s happening in the region, let alone try to influence events, is very, very difficult. What is happening at the moment has no clear trajectory.

You were in Israel this summer when violence once again erupted between Israel and Hamas. Secretary of State John Kerry has been attempting to broker a ceasefire without success. Do you believe there is hope for a resolution to this conflict, and do you see the U.S. playing a role in any resolution?

It’s been a very confusing time for the U.S. in the Middle East. The U.S. aligned itself with Qatar and Turkey in trying to stop the Israel-Gaza War, which deeply angered both the Egyptians—who felt they should be the mediators—and the Israelis, who view Qatar and Turkey as mouthpieces for Hamas. So I think the United States has had some missteps. But I predict that by next week there will be a ceasefire that will mostly stick, and the U.S. will play an important role in this. [Editor's note: Migdal made this prediction on July 31.] And I think that, after this war, both the Israelis and Hamas will be much more open to a political initiative than they were several months ago.

Why do you think Israel and Hamas will be more willing?

Israel calls these Gaza operations—in 2009, 2012, and now in 2014—"mowing the lawn," referring to the fact that the same problems grow right back. I think the Israelis are ready to talk about solutions in which there might be some more significant deals. Hamas is riding high now, having had some successes in this war, but it’s going to face a very unhappy population that has experienced massive destruction. Hamas's geopolitical position has not improved at all, so it must look for a way to improve its strategic position. I think both sides could be ready if the right initiative were brought forward. The question is whether the United States can follow up and develop an initiative that will deal with some of the outstanding problems.

Given that the Middle East is in a constant state of flux, what do you hope your readers will learn from your book?

With so many crises occurring simultaneously—in Syria, Egypt, Iran, Palestine-Israel and more—my hope is to provide readers with a frame in which they can place diverse disputes and events and understand American foreign policy in that light.

___

Shifting Sands: The United States in the Middle East was published in February by Columbia University Press.

More Stories

Is This Presidential Campaign Different?

UW History professor Margaret O'Mara provides historical context for this moment in US presidential politics.

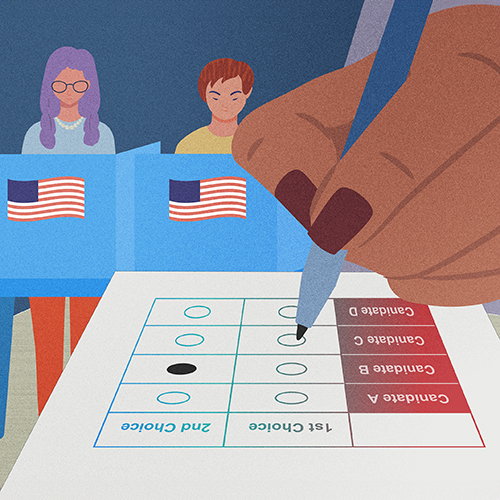

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

Making Sense of This Political Moment

To navigate this momentous election season, Arts & Sciences faculty suggest 10 books about the US political landscape.