When America’s founding fathers penned the U.S. Constitution, they limited citizenship to people similar to them: white men who owned property. But as the nation changed, so did citizenship laws—again and again and again. In a new history course, HSTAA 110: American Citizenship, John Findlay untangles the complicated factors that have influenced who can become a U.S. citizen and what that says about our nation’s values.

“I focus on pivot points where key decisions get made, usually laid down by law,” says Findlay, John Calhoun Smith Memorial Endowed Professor in the Department of History. He begins with the Revolutionary War, explaining that independence from England brought a seismic shift in responsibility, with Americans becoming self-governing after being subjects of the King. “There was this great progress away from being subjects in England, but the progress was monopolized by adult white men who owned property and weren’t Catholic,” says Findlay. “They saw themselves as the only people educated enough to be self-governing. And they believed that only men with property had enough of a stake in the system to be trusted.”

From the start, these requirements for citizenship raised concerns. “As early as the 1790s, there was a question of what is white,” says Findlay. “Does it include Asians? Does it include Italians? Some people also asked whether men without property should vote. And in the North, they began to question slavery, and whether freed slaves could ever become educated enough to become citizens. So that was built right into this nation from the beginning.”

Native Americans were also a source of debate. It was assumed by some that they could assimilate and become part of the “white” population with all the privileges that entailed—but only if they stopped living as part of a tribe, gave up any communal property rights, and became farmers who owned property.

For all the discussion about various groups and their prospects for citizenship, one major sector of the population was ignored entirely: women. In the late 1700s, full citizenship for women was unthinkable. “The assumption was that a man in her life covered a woman’s citizenship,” says Findlay. “That is, he spoke for her, protected her, watched out for her. It could be her father until she married and then her husband. The idea of a woman alone without some man to guard her interests was almost inconceivable. They had virtually no rights.” It would be another 50 years before women began to press for citizenship, and more than a century before those rights were granted by Constitutional amendment.

For most African Americans, citizenship came after the Civil War, when slavery was abolished and citizenship and voting rights were granted by law. But despite these gains, states in the South and other parts of the country denied African Americans a political voice, either using legal means—a literacy test, a poll tax—or extralegal means, such as intimidation and violence, to discourage them from voting. “That happened to a lot of groups,” says Findlay. “People of color have always experienced three steps forward and two steps back when it comes to citizenship. They have the hardest time having progress nailed down.”

People of color have always experienced three steps forward and two steps back when it comes to citizenship. They have the hardest time having progress nailed down.

Many people of color arrived in the U.S. as immigrants seeking a better life. Findlay discusses immigration at length in his course, and how it relates to citizenship. Immigrants’ success in gaining citizenship has varied greatly, depending on their country of origin and where they chose to settle in the U.S. Until the early 20th century, when a national system of immigration and naturalization was established, naturalization was handled in local courts, with some courts more lenient than others.

Findlay assigned four books in his course, providing a glimpse into U.S. citizenship through the eyes of families from four different time periods and backgrounds: a white family in New England in the 1700s; an African American family during the Civil War, living in the North but with relatives in the South; a second-generation Japanese-American woman during World War II; and Barack Obama’s autobiography. The readings served as inspiration for an assignment in which students write about their own families in the context of U.S. history.

“The assignment gets students to see their own personal stories in terms of a broader context,” says Findlay. “It takes things they might have heard around the dinner table or from grandparents and helps them identify the bigger forces that made these things possible. I want them to see their personal stories in terms of the nation.” (If they prefer, students can “adopt” a family for the project, an option popular with international students.)

Findlay is aware that the topic of citizenship cannot be covered fully in one quarter, but he hopes that the course will inspire students to explore further. “It’s a really rich topic,” he says. “I want students to come away with the clear understanding that citizenship is a malleable, complex creation that has emerged over time, that will continue to change, and that we can help to improve.”

More Stories

Is This Presidential Campaign Different?

UW History professor Margaret O'Mara provides historical context for this moment in US presidential politics.

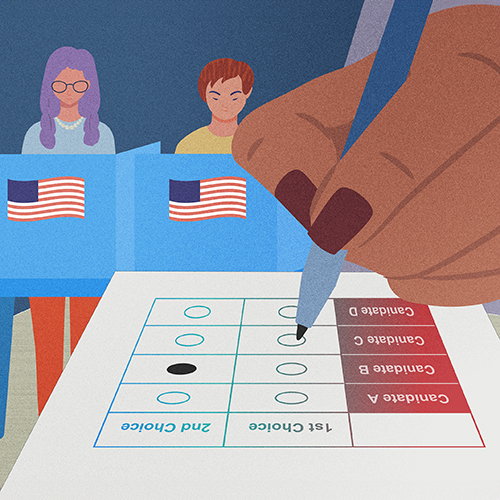

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

Making Sense of This Political Moment

To navigate this momentous election season, Arts & Sciences faculty suggest 10 books about the US political landscape.