Some say the Universe began with a 'Big Bang,' causing space to expand faster than the speed of light. Others believe a higher power summoned light and life. Still others credit a raven who stole a ball of light, spilling it as he flew off. Humans have pondered our origins for millennia, developing myriad stories and theories to explain life’s greatest mystery.

In “Cosmologies and Cultures,” an undergraduate course in the Department of Astronomy, students are introduced to the Big Bang theory of cosmology, which suggests that the Universe began with a hot, dense energy mass that began to expand 13.8 billion years ago. But students also learn other origin stories from cultures around the world. Bruce Balick, professor emeritus of astronomy, developed and teaches the course.

“I want students to understand the concept behind the Big Bang theory, but I also want them to understand that the Big Bang model is not the only [origin] story,” says Balick. “There are other stories that many people in other cultures take extremely seriously. It’s interesting to learn about these and to compare them to one another.”

Balick invited seven faculty across the College, in disciplines from classics to philosophy to Asian languages and literature, to serve as guest speakers. They shared creation stories from Daoism, Islam, Hinduism, the Bible, Greek mythology, Greek philosophy, and other religions and cultures.

Anthropology professor Stevan Harrell spoke to the class about Chinese cosmology “with some Goethe and a little E.A. Poe thrown in,” and asked students to reflect on how different modes and traditions of thought often result in the same basic ideas. “Big Bang and Steady State are present in a lot of different cultural contexts,” he says.

Classics professor Jim Clauss shared origin stories in Greek mythology, arguing that their basis in observation is something that they and science have in common. “People tend to believe that the narratives that scientists create are truths, and that mythologies from around the world are fanciful creations of people from another era who had no understanding of the world in which they lived,” says Clauss. “But when you put a humanistic investigation of mythology together with astronomy, it allows the ancient myths to be seen for what they were — genuine attempts at understanding the world based on observation.”

I want students to understand the concept behind the Big Bang theory, but I also want them to understand that the Big Bang model is not the only [origin] story.

That message came through loud and clear for Tyler Huffman, a UW senior majoring in finance. Huffman had dismissed creation theories from past cultures as “primitive ideas born from ignorance” before hearing from faculty like Clauss. “Now I see that [earlier cultures] actually had some very insightful ideas, working with the best information they had at the time,” says Huffman. “And as for the ignorance, we are still ignorant of much as well.”

Though Balick might frame it differently, he agrees that much remains unknown. Throughout the course, Balick presents the strengths of the Big Bang theory but also its limitations — because while physics and observation tell us a great deal about the evolution of the Universe, those first moments of creation remain elusive.

“We’re very proud of the Big Bang theory,” says Balick. “We think it’s substantive. We take the facts as we observe them and try to fit them into a rational story of creation. But the Big Bang theory is just that — a story built on facts.”

It’s also a story based in Western culture, building on the work of great thinkers like Copernicus and Galileo. As a result of the Cosmologies and Cultures course, Balick now believes there might be value in viewing cosmology research through the lens of other cultures.

“Fundamentally in science, there’s always the possibility that new information comes along and falsifies everything we believe now,” says Balick. “That’s at the very heart of the scientific method. The Big Bang theory is consistent with the set of facts we have now, but maybe other cultures, given the same set of facts, would come up with a whole different story. It would be exciting to see where else the data we have might fit into a brand new picture.”

More Stories

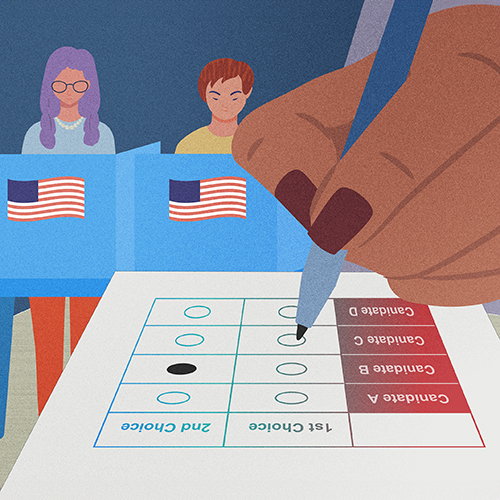

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

A Statistician Weighs in on AI

Statistics professor Zaid Harchaoui, working at the intersection of statistics and computing, explores what AI models do well, where they fall short, and why.

The Mystery of Sugar — in Cellular Processes

Nick Riley's chemistry research aims to understand cellular processes involving sugars, which could one day lead to advances in treating a range of diseases.