Two months. That’s how long Celeste Marion (BA, Psychology, 2003) planned to stay in Peru after graduating from the UW. She found a volunteer opportunity working with special needs students at a school in rural Urubamba, which seemed like the perfect short-term adventure.

Marion got the adventure part right. But short term? Not so much.

More than a decade later, Marion is still in Peru, heading Manos Unidas (MU), a nonprofit she co-founded for children with special needs.

Marion arrived in Peru with experience working with special needs children. At age 19, responding to an ad in a Seattle paper, she began doing one-on-one therapy with children with autism. Later, as a UW student, she completed a psychology practicum at the UW’s Experimental Education Unit, working with infants and toddlers on the autism spectrum. That added up to considerably more experience than any of the teachers she assisted in Peru—which is why the school asked her to stay on to train its teachers after her volunteer stint ended.

“I thought a one-year contract in a foreign country would look great on grad school applications,” Marion recalled thinking at the time. That reasoning proved true when she applied and was accepted to the UW’s graduate program in special education. But she hadn’t figured on caring so deeply about her Peruvian students. Over the next few years, she deferred graduate school twice to stay in Peru.

We wanted to teach kids to have a quality of life, and we wanted to prove to parents that their children could learn.

During that time, Marion befriended Mercedes Delgado, a teacher who worked at a state-run special education school in Cusco. “Mercedes had a really different outlook [than many Peruvians] on what she thought this population deserved,” Marion says, explaining that Peru is decades behind the U.S. in its views toward people with disabilities. “She and I would brainstorm about how we would do things differently if we had the chance.”

Taking baby steps, the two women started an afterschool program with two special needs students. (Marion taught at a bilingual kindergarten during the day.) More students came on board through word of mouth, growing the program to a dozen students within a year. But with no financial resources and few families able to pay, the program was not sustainable.

“We came to the realization that this was not going to be a for-profit business,” says Marion. “But we wanted to teach kids to have a quality of life, and we wanted to prove to parents that their children could learn. Our mission was to serve all parents, regardless of ability to pay.” Marion and Delgado successfully obtained nonprofit status and Manos Unidas was born.

The program continued to expand, outgrowing its tight quarters. At the same time, parents expressed an interest in a school rather than just an afterschool program. Marion came back to the U.S. to raise funds, and in 2009 she and Delgado opened Camino Nuevo, a school for children with disabilities in Cusco. The school began with thirty students and a six-member staff.

Despite all she’d accomplished in Peru, Marion still intended to return to the U.S. to continue her education. But a year after launching Camino Nuevo, she had what she describes as an awakening. “The school was just a year old and I was fearful that if I left, it would all collapse, all the work we’d put into it,” she recalls. “Mercedes was still working for the public school—she couldn’t risk her 22 years there and her retirement for this school that might or might not work out. So I ended up surrendering and saying, ‘Okay God, if this is where you want me, I accept it. I’m going to stop trying to move back to the United States.’”

Marion believes that was a turning point for Manos Unidas. She did visit the U.S. soon after—but all in service to the school. Friends and acquaintances across the country organized gatherings so she could spread the word and raise funds. On U.S. college campuses, she posted opportunities for volunteers. (UW students studying in Cusco have been among the volunteers.) Marion also met with specialists in everything from special education to marketing to curriculum development. “I generated a group of advisers that I could go to as mentors,” she says. “A lot of them are still in my network to this day.”

Manos Unidas now serves 75 students, with a staff of 32 and two boards—one in Peru, one in the U.S. (Manos Unidas International was created as a U.S. nonprofit in 2014.) In addition to Camino Nuevo, MU now offers an inclusive education program through which 25 students attend public school in Cusco with an MU teacher frequently on site. When students age out of these options, Manos Unidas offers a life-skills program that covers basic skills like how to shop, take the bus, and cook. In the past year, MU added Phawarispa, a vocational training program.

“The vocational training program is very exciting,” says Marion. “This is where students discover what they are capable of and how they are going to formally integrate into society. Some students are able to work independently with partial support; others need a lot of support.” Even students with severe and profound disabilities participate through an on-site work program at MU.

Marion has still more ideas. She recently worked with her two boards on a five-year “dream plan,” which includes creating an on-site preschool that brings together regular and special education students.

“I’ve gained a lot of tools and feel confident in what I’m doing now,” Marion says. “It’s fun. My brain is always going a gazillion miles an hour.”

More Stories

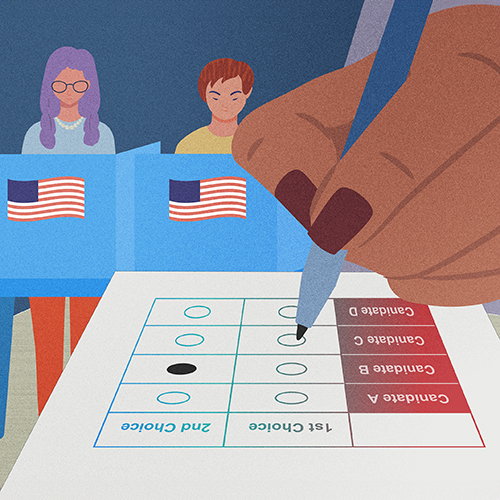

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

A Statistician Weighs in on AI

Statistics professor Zaid Harchaoui, working at the intersection of statistics and computing, explores what AI models do well, where they fall short, and why.

Finding Family in Korea Through Language & Plants

Through her love of languages and plants — and some serendipity — UW junior Katie Ruesink connected with a Korean family while studying in Seoul.