For many people, the term “human trafficking” conjures images of young girls forced into sex labor in distant lands. But human trafficking — the act of obtaining a person through force, fraud, or coercion for economic gain — is also found in industries from agriculture to domestic work to hospitality. And it’s not just a problem abroad. Human trafficking is a growing issue in the Northwest.

“Human trafficking is one of the fastest growing underground economies in the world,” says Sutapa Basu, director of the UW Women’s Center, who has studied the issue for more than two decades. “It is a $150 billion industry affecting millions of people around the globe. Two-thirds of human trafficking is in forms of labor other than sex trafficking.”

Basu and Johnna White, program manager at the Women’s Center, recently completed a state-funded study that provides recommendations for addressing human trafficking in Washington state. The 115-page report includes statistics but also stories of those victimized by human trafficking, such as Thai workers duped by a recruiter promising agricultural jobs in Washington. When the Thai workers arrived in the U.S., many having spent their life savings to pay the recruiter, their new employer confiscated their passports and forbade them to leave the premises, forcing them to work for little or no pay.

Basu has heard such stories for years. Her early research focused on sex trafficking in India, but she became aware of other forms of human trafficking long before most officials recognized there was a problem. In the early 2000s, Basu joined with former state representative Velma Veloria and victim/survivor advocate Emma Catague to approach the Washington State Legislature about human trafficking, but most officials were unconvinced that trafficking was happening domestically.

“At the time, they said, ‘That’s not a problem we have here. That’s something that happens abroad,’” Basu recalls. “Now they all acknowledge the problem here.” In fact, with guidance from Basu, Veloria, and Catague, Washington became the first state to criminalize human trafficking. Yet even now, most anti-human trafficking laws are geared to sex trafficking. The next step, Basu says, is to focus on other forms of trafficking.

When we wrote the report, we wanted to put it all out there, to plant the seeds.

Washington is particularly susceptible to human trafficking due to its international border, seaport, and large agricultural industry. The need for agricultural workers, who often work in isolated environments and face language barriers, makes that industry especially vulnerable. But the problem touches other Washington industries as well, including companies that employ factory workers halfway around the world.

“Globalization has significantly changed the scene from the 1990s to today and made this issue so much bigger,” says White. “The underbelly of globalization, the desire to create the cheapest goods, has created more sweatshops and more human trafficking situations. And it means that all of the goods we consume are more likely to have been touched by trafficked labor. The supply chains have gotten so much more complex, with layers and layers of contractors.” Even within Washington’s local supply chains, human trafficking has been reported in 18 counties within numerous industries.

Companies sometimes dodge human rights concerns by hiring locals to oversee factories in other countries, washing their hands of the issue. The Women’s Center report recommends that companies be responsible for their supply chain all the way to the bottom, using independent third-party monitoring to ensure that factories are compliant. The University of Washington already works with a third-party monitor, the Worker Rights Consortium, which checks on factories in which Husky-branded clothing and other merchandise is made.

Basu realizes that corporations, even those committed to anti-trafficking efforts, may balk at the report’s recommendations. Some companies conduct in-house monitoring of their own supply chain and insist that is sufficient. Basu and White believe that monitoring by a neutral third party is important, but they tread lightly in the report. “Corporations don’t want to be legislated,” admits Basu, “so one of the things we’ve done in the report is to focus on the public sector, including state universities and state procurement policies. If we start by developing anti-human trafficking policies for the state’s public institutions, down the road we can address the private sector.”

Basu has been at this long enough to know that one set of recommendations will not change everything. Yet the fact that the State of Washington funded the study, and that many public leaders are concerned about human trafficking, is cause for optimism.

“When we wrote the report, we wanted to put it all out there, to plant the seeds,” says Basu. “The report is a beginning stage and now the State can build on it. Knowing the system, the process will move slowly, but we plan on seeing some of our recommendations become law. It’s going to happen. It’s just a matter of time.”

The Women's Center anti-human trafficking report is viewable online. To learn how you can support the Women's Center's anti-human trafficking work, contact Heather Hudson at hzhudson@uw.edu or 206-685-7570.

More Stories

Is This Presidential Campaign Different?

UW History professor Margaret O'Mara provides historical context for this moment in US presidential politics.

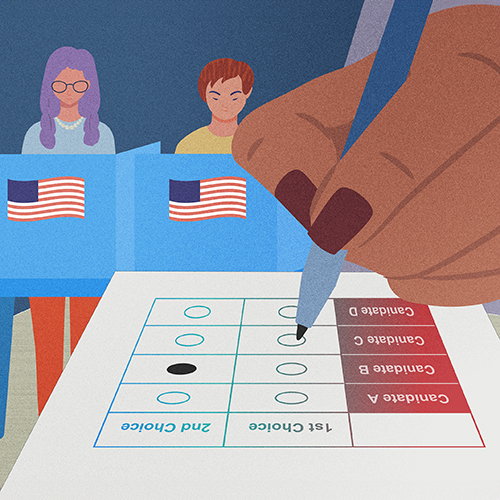

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

Making Sense of This Political Moment

To navigate this momentous election season, Arts & Sciences faculty suggest 10 books about the US political landscape.