Margaret Walrod of the Republic of Cyprus had heard enough. After a grueling day of negotiations with the European Union, Turkey, and others, the parties had made no progress in resolving the Cyprus conflict. Now Walrod was meeting with Turkish Cypriots — a meeting brokered by a United Nations official — and it was going no better. So without warning, she walked out.

“My actions didn’t sink in until I had already left the room,” Walrod recalls. “I kept thinking, ‘What did I just do? What did I just do?’”

Fortunately there were no international repercussions. That’s because the two-day negotiation was a simulation — the centerpiece of an International Strategic Crisis Negotiation course taught by Robert Pekkanen, UW professor of international studies. The course is offered through the Jackson School of International Studies’ MA in Applied International Studies (MAAIS) program.

MAAIS, entering its fourth year, is designed for mid-career professionals who seek to engage more effectively with government, nonprofit, and business sector leaders in tackling critical global challenges. Pekkanen and MAAIS director Jennifer Butte-Dahl sought a capstone experience that would allow MAAIS students to apply all their newfound skills. When they learned that the U.S. Army War College develops crisis scenarios for colleges to use for simulated negotiations, they knew they’d found their partner. Other colleges offer the two-day simulation as an extracurricular activity, but MAAIS developed an entire course around it to ensure that students make the most of the opportunity. In addition to Pekkanen, the Jackson School brings in high-level mentors from the worlds of diplomacy and business to support the students during the negotiations.

The U.S. Army War College offers a variety of crisis scenarios to choose from. Butte-Dahl and Pekkanen chose the South China Sea scenario the first two years, but switched to Cyprus this past year. “All the stars aligned,” explains Butte-Dahl. “Ambassador John Koenig, former ambassador to Cyprus, just retired from the Foreign Service and moved to Bellingham. Also nearby is Portland State University professor Birol Yesilada, who has been involved in Cyprus negotiations forever. So we had all this great expertise locally.

Cyprus has been a divided island rife with conflict since the 1960s. Turkish forces invaded in 1974, and now the north is held by Turkish Cypriots while the south — the Republic of Cyprus — is mostly Greek. Negotiations held this June in Geneva failed to resolve the conflict. The scenario created by the U.S. Army War College is set in 2018, at the midpoint in a series of fictitious negotiating sessions, with all parties meeting to seek common ground under the auspices of the United Nations.

For the simulation, students were divided into seven teams representing the Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities, the European Union, and the governments of Britain, Turkey, Greece, and the U.S. From the start, team members sat together, quickly developing allegiance to their group. Everyone was given a hefty packet of background materials on Cyprus — old United Nations resolutions, maps, past agreements — with one twist: each team was given specific negotiating instructions outlining what it should be trying to achieve, but none was privy to the other teams’ instructions.

Negotiations are complicated, messy things. Everyone wants something different.

“Negotiations are complicated, messy things,” says Butte-Dahl. “Everyone wants something different. You may know what your negotiating position is, but you may not be quite sure of what other parties are trying to get out of these conversations. It’s a process of trial and error. The students come in the first day thinking they know what’s going to happen and how it’s all going to unfold, and they build a strategy around it and then their strategy goes out the window. It happens every year.”

Before the simulation, the students spent several weeks drafting remarks and planning negotiation strategy for their team. Though their immediate concern was the simulation, the same skills will benefit them for years to come. “It’s unlikely that any of them will work in a professional capacity on the Cyprus issue specifically,” says Pekkanen, “but they are very likely to work in small groups, need to exercise leadership, and be good at communication and negotiation.”

As the two-day Cyprus simulation began, the excitement and nerves were palpable. Koenig, Yesilada, and other experts mentored individual teams. Three officers from the U.S. Army War College handled the logistics as teams negotiated in different locations throughout the two-day exercise. At the center of it all was Ambassador Thomas Pickering, a long-time friend to the Jackson School, who played the role of the United Nations Secretary General’s advisor on Cyprus and served as mediator in all the negotiations. “Ambassador Pickering is one of the most distinguished ambassadors alive today, so his willingness to participate in this has been amazing,” says Butte-Dahl. “He’s the consummate diplomat, and he’s seen it all.”

Amidst all the tumult, Pekkanen continued to teach, pulling students aside as needed to shed light on their actions without intervening. “I didn’t tell them, ‘You should really go talk to Turkey,’” Pekkanen explains. “What I would say is, ‘Why was that a successful negotiation? What happened in there?’ If there’s a moment when I can bring them into learning about what they’re doing as they are doing it, that’s great.”

One of those teachable moments came when Walrod stormed out of the negotiation session. It was a bold move, especially given that the session was presided over by Ambassador Pickering, whom Walrod — who works for the State Department in real life — had been particularly honored to meet. But when Pekkanen spoke with Walrod about her exit, it was to offer praise rather than criticism.

“I don’t think the delegation would actually have stormed out at that point in the negotiation, but I didn’t care,” says Pekkanen. “I loved it, because she pushed out of her comfort zone to do something that wasn’t natural. This was an opportunity to experiment with negotiation tactics. That’s what I want to see in a simulation--students getting to learn and explore things in a way they can’t in a typical class environment and might not be free to experiment with in their jobs.”

As it turned out, that exit was not Walrod’s only bold move. Ten minutes before the closing session, she had a secret meeting in a restroom with a representative from the Turkish Cypriot side to finalize an agreement.

Bathroom negotiations aside, the Cyprus conflict was not resolved over the course of the exercise. But that, says Butte-Dahl, is beside the point.

“We tell students from the beginning that the goal is not to solve the crisis. What matters is what they learn through the process,” says Butte-Dahl. “The course and simulation allow us to link the students’ academic experience to the world in which they are living and working. It’s a great way for them to try, and perhaps fail, before they have to do it again in the real world, with much higher stakes.”

. . .

For more about the MAAIS program, visit www.appliedinternationalstudies.uw.edu.

More Stories

Is This Presidential Campaign Different?

UW History professor Margaret O'Mara provides historical context for this moment in US presidential politics.

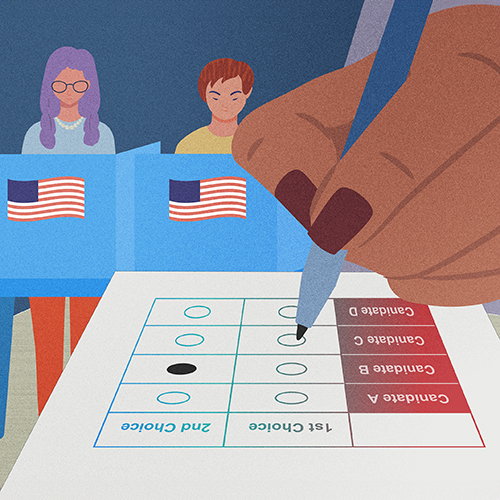

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

Making Sense of This Political Moment

To navigate this momentous election season, Arts & Sciences faculty suggest 10 books about the US political landscape.