Jason was flummoxed. As a medical student he’d met with patients before, but this time he couldn’t decipher what the patient was trying to say. She was unable to communicate clearly because of aphasia, a communication disorder that makes word-finding difficult. Both doctor and patient were frustrated — until Jason remembered strategies he’d learned in a training session about communication disorders.

The Department of Speech and Hearing Sciences (SPHSC) offers training to UW medical students each year to improve their interactions with patients with communication disorders. During the two-hour session, the medical students have opportunities to practice what they learn, with Speech and Hearing Sciences students role-playing as patients. About 150 medical students and 25 SPHSC students participate each year.

“We knew we wanted to give the medical students interactions with patients who struggle to communicate,” says SPHSC lecturer Michael Burns, who leads the training with Carolyn Baylor, adjunct associate professor of SPHSC and associate professor of rehabilitation medicine. “We realized we have an army of students in our department who are learning all about these communication problems, so we now train them to take on the role of the patient.”

The SPHSC students enroll in a one-credit course, Patient-Provider Communication, that not only trains them for their role as patients but explores communication issues in medical settings and the role of speech-language pathologists in addressing them. It’s a topic Burns knows well. He spent years working as a speech-language pathologist in medical settings, witnessing poor interactions between patients with communication disorders and their providers. For his dissertation research, he interviewed doctors, patients with communication problems, and their family members about the challenges they face.

SPHSC’s medical student training focuses on two common disorders, often caused by a stroke: aphasia, a word-finding problem, and dysarthria, a weakness in many of the muscles involved in speech. Each disorder presents unique challenges. Patients with dysarthria are often able to find the right words but can’t speak clearly, so offering a white board, a pen and pad, or a sheet with the alphabet can make all the difference. But that approach won’t necessarily help patients with aphasia, who typically struggle to find words whether they are speaking or writing. For them, it’s best to avoid open-ended questions that make answering difficult. Instead, simplifying questions or using a sheet with medically related pictures can be helpful, enabling the patient to point to the pertinent image, such as a pill bottle if the concern is medication.

Patients typically know what they want to say, but sometimes the doctor just isn’t unlocking the right pathway to let them do that.

That sounds simple enough, but identifying a communication problem and devising an appropriate solution can take practice. Burns spends 30 minutes talking to the medical students about strategies, which they then use in the role-play exercises. “That’s the most powerful piece,” Burns says. “We give them a ton of tools and they often say ‘Yeah, I get this, it’s easy,’ but when we put them in front of one of our SPHSC students trained to struggle to communicate, they typically freeze. They initially can’t figure out what they’re supposed to do. It happens every time. They often find out that it’s harder than they thought.”

The students participate in two or three role-play scenarios. Each time, the medical students have ten minutes to figure out the patient’s current health concerns. The experience is eye-opening — not only for the medical students, but also for the SPHSC “patients” who experience the frustration of not being understood.

“Patients typically know what they want to say,” says Burns, “but sometimes the doctor just isn’t unlocking the right pathway to let them do that. Our students get to experience that.”

At the end of the training, students shed their roles to gather for a debrief. The medical students share what was difficult and what got easier; the SPHSC students offer feedback and suggestions based on their observations as patients. “I always tell our Speech and Hearing students that they often know more about this topic than medical students do, and that they have valuable advice to give,” Burns says. “This training helps them see that.”

While patient-provider communication training occurs in nearly all medical schools, few are discussing and including patients with communication disorders. Burns and Baylor hope to share their approach with medical schools in the U.S. and abroad through an online module they are developing. They know that awareness of communication issues can greatly improve the healthcare experience for patients.

“If doctors take the first few minutes to figure out how a patient communicates, the rest typically will go much easier,” Burns say. “As long as they recognize there’s a problem and try to address it, that’s all their patients are looking for. Patients don’t expect doctors to be perfect at this. But to ignore the problem and pretend it’s not happening — that’s not going to work. You have to do something different.”

More Stories

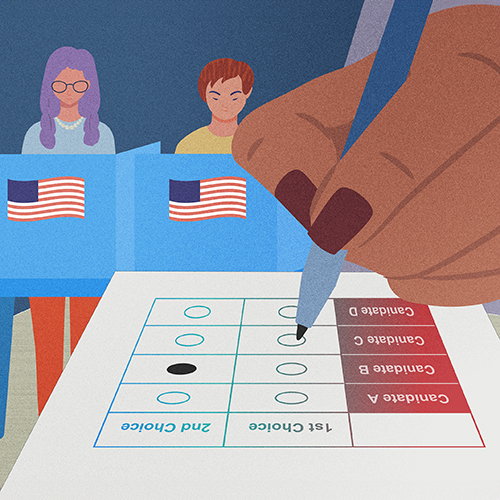

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

A Statistician Weighs in on AI

Statistics professor Zaid Harchaoui, working at the intersection of statistics and computing, explores what AI models do well, where they fall short, and why.

The Mystery of Sugar — in Cellular Processes

Nick Riley's chemistry research aims to understand cellular processes involving sugars, which could one day lead to advances in treating a range of diseases.