On a balmy August afternoon, UW students watched dozens of cedar canoes arrive at West Seattle’s Alki Beach during the annual Tribal Canoe Journeys. Days later, they observed their professor singing with her tribe in full regalia in Puyallup, Washington. It was all part of a memorable summer course, Indigenous Peoples and Cultures of the Northwest Coast, offered by the Department of American Indian Studies (AIS).

During the academic year, the course has an average enrollment of 90 students. But summer enrollment is considerably lower, creating possibilities for meaningful experiential learning. “It’s the first time I’ve taught a class that is mostly set outside the classroom,” says Charlotte Coté, AIS associate professor and a member of the Tseshaht tribe, part of the Nuu-chah-nulth Nation on Vancouver Island. “I wanted my students to experience the cultures rather than just reading and writing about them.”

Students came to the summer course with a range of backgrounds and majors. Most had minimal contact with Indigenous culture. Over four weeks, they learned about everything from Indigenous plants to gender roles in tribal communities through assigned readings, guest speakers, and visits to sites like Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center and the Seattle Art Museum.

I wanted my students to experience the cultures rather than just reading and writing about them.

With their very first assignment, the students observed their surroundings through a new lens. After learning about Indigenous plants of the Northwest coast, they completed a self-guided plant walk in which they documented the plants around them, researching their Coast Salish names and uses. Many students did their plant walks on the University of Washington’s Seattle campus.

“They were very surprised by the environment they took for granted,” says Coté. “They discovered that plants they had walked past every day were significant in the diets of the coast Indigenous peoples, having either nutritional or medicinal qualities. That really opened their eyes.”

The students learned more about their UW surroundings when guest speaker Ken Workman, a Duwamish tribal member, visited class to discuss the history of the Duwamish people on whose land the University is located. Workman also spoke about the importance of cedar to Indigenous peoples of the Northwest coast, sharing how the traditional Duwamish burial practice was to wrap the deceased in cedar bark and place them in cedar trees. As the body and wrapping decomposed, nutrients would feed the tree. “As Ken told the story, he pointed to a cedar tree and said, ‘My ancestors are literally in those trees,’” says Coté. “That blew the students’ minds.”

Coté continued the cedar theme with a session on weaving with cedar. A basket weaver herself, she brought samples of cedar bark before and after it had been stripped and soaked to be pliable for weaving. She then demonstrated weaving methods and asked students to start a simple weaving project, to be completed by the end of the quarter.

The emphasis on cedar reflects the essential role cedar trees have played in the lives of Northwest peoples, providing raw material for everything from housing to clothing to the canoes that were once their main mode of travel. “Cedar was used for all aspects of our lives, utilitarian and ceremonial, including ceremonial regalia like rattles, drums, and headdresses,” says Coté. “It has a spiritual quality to it because of how it helps sustain our cultures and traditions.”

Those traditions are on full display during Tribal Canoe Journeys, an annual event that brings together dozens of Northwest tribes. Participants travel by canoe, with some paddling for weeks over great distances to reach their final destination. They stop at Native nations along the way until they reach the host nation — this year, the Puyallup tribe. That nation hosts a celebration that includes the sharing of food, songs, dances, and gifts. It was there that Coté joined her Tseshaht community in a paddle song and the traditional protocol of thanking the host nation with gifts.

Coté’s students wrote about their professor’s participation — and everything else they experienced during the four-week course — in assigned journals, often responding to prompts provided by Coté to encourage meaningful reflection. “In their journals, the students shared how powerful the singing and dancing was at the Tribal Canoe Journeys, and how they were welcomed as non-Native people,” says Coté. “They were very surprised at how people made them feel like they belonged there.”

For their final field trip, the class visited the Seattle Art Museum to view Double Exposure, an exhibit that challenges stereotypes about Native Americans. Coté, who served on the advisory committee for the exhibit, hopes that not just the exhibit but the entire course challenged preconceived notions the students might have had.

“I hope that now when they see a Native person or travel through certain areas, they’ll be able to relate to the Indigenous experience of that person or that land,” says Coté. “More than anything, I want my students to have a respectful appreciation of Indigenous people’s culture. Because we’re still thriving and we still have vibrant cultures. We remain very connected to the traditions that make us distinct and that connect us to our homeland.”

More Stories

Is This Presidential Campaign Different?

UW History professor Margaret O'Mara provides historical context for this moment in US presidential politics.

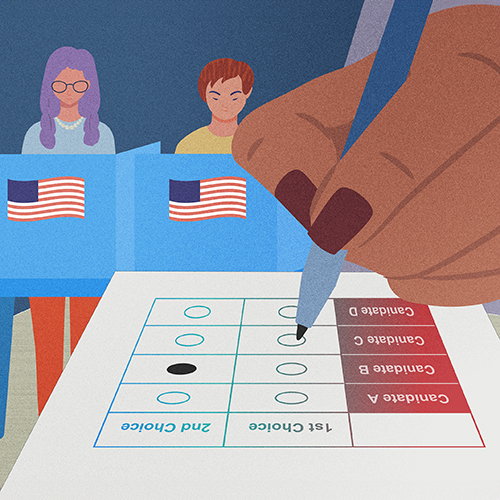

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

Making Sense of This Political Moment

To navigate this momentous election season, Arts & Sciences faculty suggest 10 books about the US political landscape.