If you time-traveled back to the early 1800s, to the future site of the University of Washington, all around you people would be speaking an unfamiliar language — Southern Lushootseed. Spoken by Coast Salish tribes for thousands of years, the language was all but lost by the late twentieth century. Now Southern Lushootseed can once again be heard on campus thanks to a course offered by the Department of American Indian Studies (AIS.)

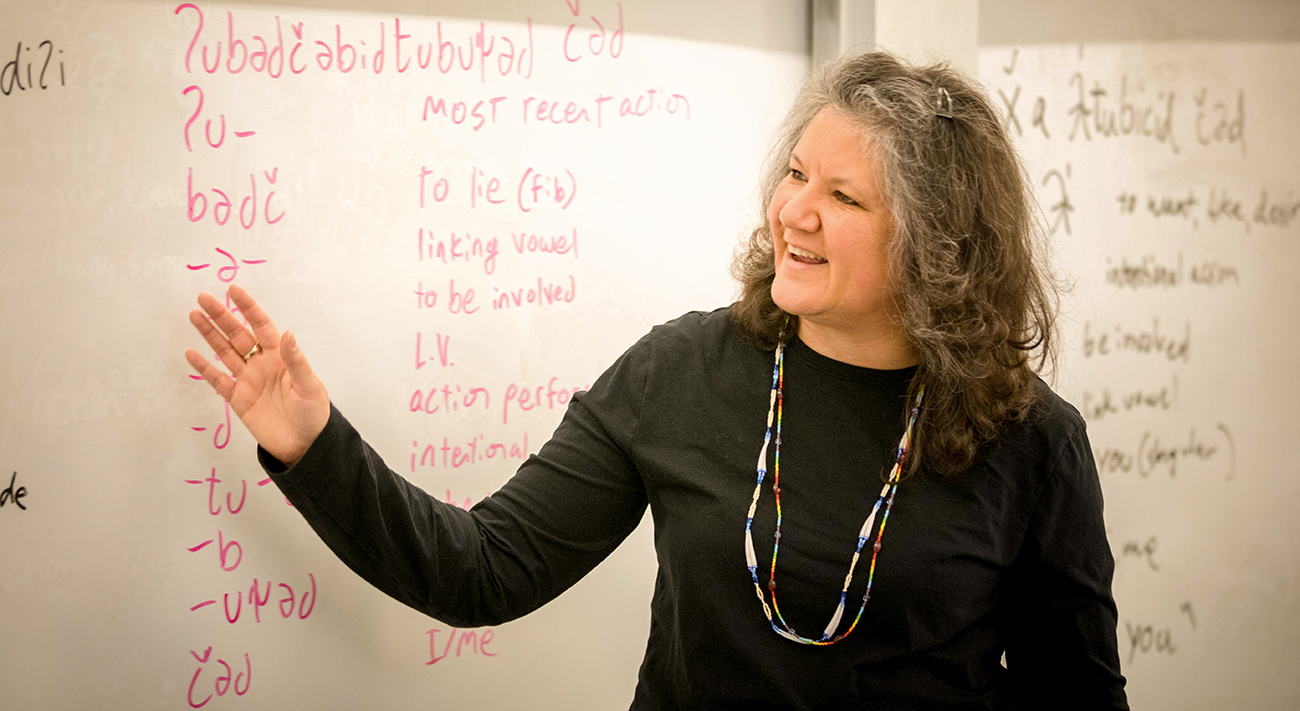

Tami Kay Hohn, AIS lecturer and member of the Puyallup tribe, teaches Southern Lushootseed through a three-course language sequence being offered for the first time at the UW. (Northern Lushootseed, a related dialect, was taught by Vi Hilbert at the UW in the 1980s.) The sequence fulfills the University's world language requirement.

Southern Lushootseed was traditionally spoken by the peoples of Duwamish, Snoqualmie, Muckleshoot, Puyallup, Nisqually, Squaxin Island, Suquamish, and their neighbors. Only a handful of first language speakers remained by the 1990s — all have since passed away — and the language was at risk of disappearing. That’s when Hohn and others began preserving the language using old documents and recordings as source materials, with the ultimate goal of making Southern Lushootseed a living language again. “To bring a language back to life requires people speaking it,” says Hohn. “Lots and lots of people who fully understand the intellect of the language and can speak it every day.”

To bring a language back to life requires people speaking it. Lots and lots of people who...can speak it every day.

To that end, Puget Sound tribes have spent years establishing robust language programs in their own communities. Once those programs were well established, it was time to think more broadly. So when AIS chair Christopher Teuton proposed a weekly language table in Southern Lushootseed at the UW in 2017, Hohn and colleague Nancy Jo Bob, a member of the Lummi Nation, were more than willing to travel to the Seattle campus each week to lead the effort.

The language table attracted a dedicated group of 15-20 students, staff, faculty, and community members. They continue to meet weekly, with new arrivals welcome. The table’s popularity paved the way for the more formal three-course sequence this academic year.

“I’ve been deeply interested in helping to bring back the Lushootseed language to the University of Washington,” says Teuton. “I see my role as a catalyst, to move things along. I think it’s absolutely imperative that this flagship university in the state of Washington offer the language of this place.”

Students have a variety of motivations for studying Southern Lushootseed. AIS major Karen Elliott, who hopes to learn and teach the languages of her own Haida and Tlingit tribes in the future, appreciates how Lushootseed reflects Coash Salish culture, providing insights on everything from social structure to the relationship with the environment. “I have been learning so much about myself through this class,” Elliott says. “In my progress toward Lushootseed, I can’t help but think of how my own tribes’ languages hold the key to how I’m supposed to live my life.”

UW junior Reidar Kelstrup discovered Southern Lushootseed through his interest in language and Indian affairs. After attending the language table last year, he was hooked. “As a non-Native, I thought the only way to appropriately involve myself in Indian affairs would be to engage with the communities whose traditional homeland I live in,” Kelstrup says. “I began studying Lushootseed because that is the language traditionally spoken in the place I call home.” The experience inspired Kelstrup, an AIS major, to add a second major in linguistics. He now plans to study linguistics at the graduate level. “My experience with Lushootseed definitely got me considering my language hobby more seriously,” he says.

For language enthusiasts like Kelstrup, Lushootseed is particularly compelling. It has 42 sounds, including clicking sounds and throaty sounds not found in English. “If students haven’t used those muscles because they are English speakers, they have to form the muscle development,” says Hohn. “It takes practice and exercise to strengthen them.” Teuton, who attends the language table, can attest to that. “After you’re done practicing, you feel like your throat and mouth got a workout,” he laughs.

Beyond its unique vocalizations, Southern Lushootseed’s alphabet, grammatical structure, and vocabulary are completely different than English. “The language looks so different that people get intimidated just by looking at it,” says Hohn. “But fairly quickly they realize that it’s doable.”

Hohn has committed to teaching Southern Lushootseed at the University for two years. Teuton would love to see a permanent position created, with opportunities for more advanced study. Already he is seeing the impact of the University’s Lushootseed offerings. Some students now chat in Southern Lushootseed while visiting and working at wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ Intellectual House, home for the Native American community at the UW.

“That was not true when I arrived at the UW four years ago,” Teuton says. “Now students are speaking the language and it is taking root. Once it becomes an expectation that you speak Southern Lushootseed in a space like wǝɫǝbʔaltxʷ, that’s how a language lives. And that’s very exciting.”

More Stories

Is This Presidential Campaign Different?

UW History professor Margaret O'Mara provides historical context for this moment in US presidential politics.

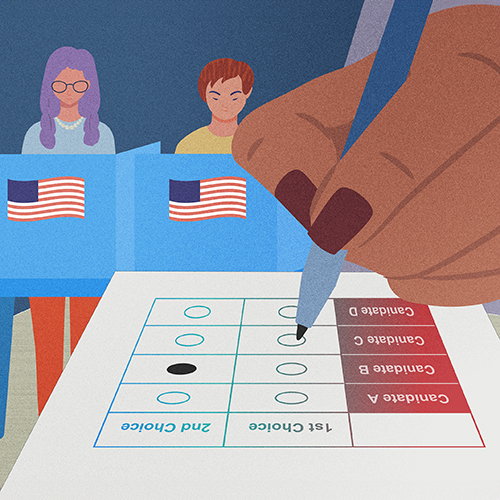

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

Making Sense of This Political Moment

To navigate this momentous election season, Arts & Sciences faculty suggest 10 books about the US political landscape.