When American leaders discuss how immigration has shaped the United States, they never mention musical theater. Perhaps they should.

“There would be no Broadway musicals if America’s doors had not been opened wide to immigrants,” says David Armstrong, affiliate instructor in the UW School of Drama, who views the rise of the Broadway musical as largely an immigration story. Armstrong shares that history in a new course, The Broadway Musical: How Immigrants, Queers, Jews, and African Americans Created America’s Signature Art Form.

Armstrong’s lifelong passion for musical theater began when he was just seven years old. His mother, intending to take him and his sister to see the film Dumbo, mistakenly took them to the film musical Gypsy instead, about a stripper. He was mesmerized.

“Fortunately my mother was not uptight, so she didn’t make us leave the theater,” laughs Armstrong, whose career in theater has included 18 years as executive producer and artistic director of Seattle’s 5th Avenue Theater. “I’m interested in all kinds of theater, but I think musical theater is the most impactful because it affects us on all levels — intellectual, physical, and emotional.”

Armstrong explains that musical theater got its start following a huge wave of Irish immigration in the late 1800s. Of particular importance was George M. Cohan, whose grandparents were among those Irish immigrants. Cohan was a writer, director, producer, and performer who launched musical theater as a distinct genre in the early 1900s. “This was the era of ‘Irish need not apply,’” says Armstrong. “Discrimination against Irish immigrants was rampant. When George M. Cohan stood on stage and sang ‘I’m a Yankee Doodle Dandy,’ that was a huge political statement.”

Around the same time, Jewish immigrants arrived from Eastern Europe and African Americans moved to New York from the South, further developing the art form. Like the Irish, these groups faced discrimination and had few opportunities for advancement. But the middle- and upper-class audiences that attended theater performances looked down on performing as a profession, leaving that field wide open for the lower classes. For those who had talent, musical theater was a way out of poverty.

There would be no Broadway musicals if America’s doors had not been opened wide to immigrants.

That was the case for Irving Berlin, who came to the U.S. from Russia at age five and grew up dancing for pennies on the Lower East Side. With little education and no formal musical training, Berlin became America’s songwriter laureate, writing thousands of songs including God Bless America, White Christmas, and Easter Parade, as well as 17 complete scores for Broadway musicals and revues, including Annie Get Your Gun.

Renowned songwriter Cole Porter and other members of the queer community were also among those working at the highest levels of musical theater from the start. “For the queer community, the early 20th century was a very open period,” says Armstrong. “People were not quite openly gay, but almost. They were valued and largely accepted in that world.”

Armstrong features all of these musical theater pioneers in his course, weaving in the huge influence of African American writers and performers, and the less visible but significant contribution of women working as songwriters, lighting designers, and choreographers. He then traces the bumpy road of musical theater, which has included periods of great popularity followed by decline and evolution.

The genre’s first decline came during the Great Depression, when only the sophisticated elite could afford tickets. The number of productions dropped by half, and shows became more urbane and sophisticated to attract an audience. Hollywood began producing film musicals during this period, broadening the audience. Then in 1943, Rogers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma came to Broadway. It integrated its story, song, and dance more cohesively than any show before, ushering a Golden Age for musicals that would last nearly 30 years.

“All of the classics come from that period,” says Armstrong, who explains that before Oklahoma, operettas, revues, and musical comedies were entertaining but very loosely constructed. Oklahoma’s new form and phenomenal success led to other shows built around story and characters. “It was an evolution, but it felt more like a transformation,” says Armstrong. “It became a much more impactful art form.”

After this class, these students will never see musicals the same way again. ...It is our great American art form, and I’m thrilled to share it.

Another shakeup came with the Vietnam War, when a growing cynicism led to shows like Cabaret and Sweeney Todd that featured darker themes and antiheroes. Broadway composers initially chafed at the popularity of rock and roll music, but eventually incorporated rock and other pop styles, a trend that has continued. Today’s widely successful Hamilton, featuring hip hop music, has ushered in another Renaissance and introduced a new generation to Broadway.

Most students are familiar with Hamilton, but homework assignments introduce them to shows that came before. Armstrong assigns film versions of selected musicals, often pairing shows from different eras to explore thematic similarities. (Both Gypsy and Hairspray, for example, feature transgressive women who refuse to follow the rules.) He also presents clips in class, and has students attend a UW production and two musicals at the 5th Avenue Theater during the quarter — the latter at a fraction of the usual price thanks to his connections.

Through this immersion, students discover common themes in musicals. The most ubiquitous is race, from Showboat in the 1920s to West Side Story in the 1950s to Hamilton today. “Over the 120-year history of musical theater, about 37 musicals have dealt with race as principal subject matter,” says Armstrong, who spends a full class session exploring the theme.

Toward the end of the quarter, students will dream up their own ideas for a new musical, which they will pitch to a panel of industry professionals, hoping to demonstrate how their story would benefit from this unique form of storytelling. The students are unlikely to come up with the next Hamilton, but Armstrong hopes the class project, and the course, will forever change the way they look at musicals.

“After this class, these students will never see musicals the same way again,” says Armstrong. “They will have an appreciation for the form, and see it as an important cultural touchstone. It is our great American art form, and I’m thrilled to share it.”

More Stories

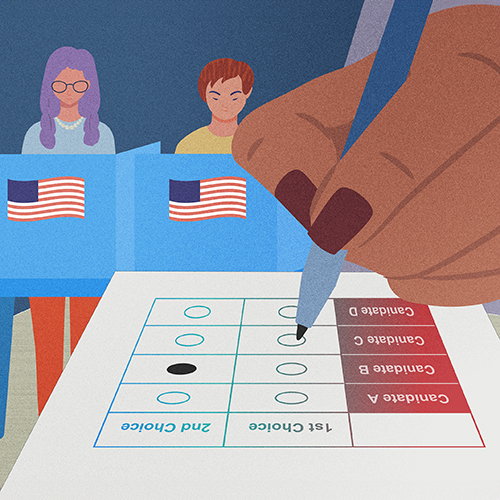

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

Dancing Across Campus

For the dance course "Activating Space," students danced in public spaces across the University of Washington's Seattle campus this spring.

Read or Listen to Faculty Favorites

Looking for book or podcast recommendations? We asked faculty who've been featured in Perspectives newsletter during the past academic year to suggest a personal favorite.