“You’re the microplastics girl!”

Lyda Harris was hiking in the North Cascades when a stranger called out to her, recognizing her from a public talk she’d presented on microplastics six months earlier.

The hiker’s greeting was fitting for Harris, a doctoral student in the UW Department of Biology. She has studied microplastics — plastics less than five millimeters in length — for more than a decade, beginning with a high school science fair project in 2009. She planned that project soon after concerns about microplastics began hitting the news.

We can solve this problem. It’s just a matter of how much people care about it.

Some microplastics are small from the start, such as granules added to face wash or toothpaste. Others start out larger. Plastic bags break apart, and materials with synthetic fibers — fleece jackets and yoga pants, for example — release fibers into the water every time they are washed. “We’ve found microplastics in the ocean, in tap water, in the arctic, and in snow in the mountains of Colorado,” says Harris. “Collect rainwater and they’ll be in there too, after being swept up into the atmosphere.”

The severity of microplastics pollution and its impact on sea life are still unclear. To search for answers, Harris has turned to mussels, working in the lab of Emily Carrington, professor of biology. Mussels bring water into their bodies and filter it for algae, their main food source, before flushing it back into the ocean. A mussel measuring 45 mm — less than two inches — can filter up to one gallon of water per hour. “They are constantly cleaning the water,” says Harris.

Because mussels ingest microplastics, Harris has analyzed their stomach contents at 15 coastal sites from Tacoma to the northwest tip of the Olympic Peninsula to quantify microplastics contamination in the Salish Sea. She conducted a similar study in the waters bordering San Diego. She also has studied how microplastics affect physiological and ecosystem functions, including how microplastics slow the rate at which mussels filter water — with the implication that a slower filtration rate leads to both less food ingested and less water cleaned.

Harris’s research is ongoing, and has been possible thanks to support from Friday Harbor Labs and the Department of Biology. Biology support has included the Washington Research Foundation and Benjamin Hall Endowment for Graduate Student Excellence in Biology, the Edmonson Award, the Robert T. Paine Experimental and Field Ecology Endowed Fund, the Wingfield/Ramenofsky Award, and travel awards from the Carrington lab. “My research would not have been possible without this support,” Harris says. “It helps that mussels are inexpensive to study, being abundant and close by.”

Despite their centrality to Harris’s current research, mussels did not interest Harris before graduate school. “Before I started at the UW, people warned me not to work with an organism I’m in love with, because I’ll get really sick of it,” Harris laughs. “I definitely wasn’t in love with mussels. But I’m very fond of them now.”

Harris is quick to add that seafood lovers should not hesitate to eat Northwest mussels. Her research has found that microplastics contamination is low in the waters off the Washington coast as compared with other places. That’s good news for the Northwest, but it doesn’t lessen her concern. She sees the problem as global and growing, which is why she has become a spokesperson for the importance of minimizing our use of plastics.

Audiences are paying attention. In addition to being recognized as “the microplastics girl” on a North Cascades hike, Harris was similarly recognized while visiting a winery on Whidbey Island. “I’m glad I’m the microplastics girl, not the mussels girl,” she jokes. “I’m glad that what I said has stuck with people a bit.”

Harris’s message? We need to change our mindset about plastic.

“We’re producing more plastic than ever,” she says. “The average plastic bag is used for twelve minutes, but it will be around forever. There needs to be a massive policy shift.”

The European Union is beginning to act, with the European Parliament voting overwhelmingly to ban, by 2021, single-use plastic items for which alternatives exist on the market. And companies like REI and Patagonia are working to make their products more environmentally friendly. But the U.S. government is not yet on board. Though three U.S. states — New York, California, and Hawaii — have banned single-use plastic bags (and in Washington state, Seattle has a ban on plastic bags and plastic straws), ten other states have passed preemptive bans on banning plastic bags.

“That’s depressing,” Harris admits. Yet she refuses to lose hope.

“If we really want to, we can do something about this,” she says. “We can solve this problem. It’s just a matter of how much people care about it.”

More Stories

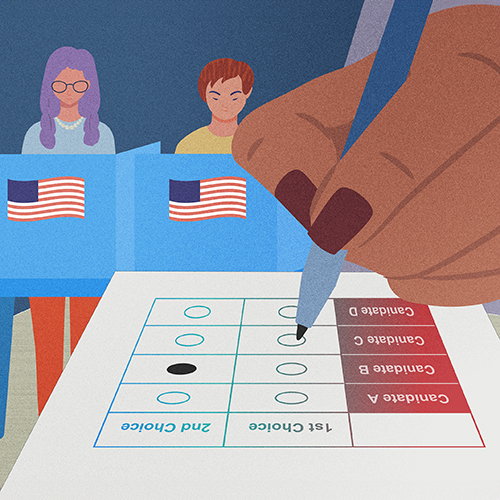

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

A Statistician Weighs in on AI

Statistics professor Zaid Harchaoui, working at the intersection of statistics and computing, explores what AI models do well, where they fall short, and why.

Finding Family in Korea Through Language & Plants

Through her love of languages and plants — and some serendipity — UW junior Katie Ruesink connected with a Korean family while studying in Seoul.