Christian Sidor clutches a large box as he enters a classroom at the new Burke Museum. He’s about to teach his vertebrate paleontology course, and the box holds a valuable specimen from the Burke’s paleontology collection: a fossilized amphibian skull from the Triassic Period. Students in the class have the opportunity to examine the skull, even touch it, for a visceral connection to a creature that lived 245 million years ago.

“We use real fossils in our undergraduate labs,” says Sidor, professor of biology and Burke Museum curator of vertebrate paleontology. “I have to remind the students that these specimens are extremely rare and fragile. I wouldn’t want to transport them across campus and risk damaging them, but with dedicated classrooms at the Burke, it’s possible to share the collection. It’s pretty incredible that an undergraduate class has this kind of access.”

The same is true for many classes at the Burke, from an art history class on Native American art to a biology class on the evolution of terrestrial ecosystems. Most classes are taught by Burke curators, who hold joint appointments in academic units. (Eleven of the museum’s twelve curators are faculty in the College of Arts & Sciences.) The joint appointments translate to exceptional opportunities for undergraduate and graduate students, including access to the 16 million biological, geological, and cultural objects in the museum’s collections.

It’s pretty incredible that an undergraduate class has this kind of access.

Holly Barker, principal lecturer in the Department of Anthropology and curator of Oceanic & Asian culture, has developed several undergraduate anthropology courses specifically for Burke classrooms. This quarter she is teaching “Decolonizing Museums,” which takes a hard look at how museums historically built a significant portion of their collections by plundering other cultures. Students see firsthand how the Burke is trying to right those wrongs through collaborative relationships with heritage communities represented in its collection.

“I don’t want to give an impression that there’s been a neat, tidy reckoning with the past,” says Barker. “We still have much work to do. Our emphasis is building respectful relationships with communities so that we can begin to do that reckoning work, that acknowledgement work. When I think of my job as a curator, I think primarily it’s to listen.”

The involvement of heritage communities includes University of Washington students. Seeing students connect with their heritage at the Burke is always moving for Barker. Recently she witnessed Tongan student Tupou Vaenuku’s emotional response to holding Tongan artifacts from the collection. “As a Tongan-American, being able to interact with the Tongan collections sparked motivation in me to learn everything I can about my own heritage,” says Vaenuku. “It led me to begin research with Holly on cultural identity in Tongan communities and how connecting with our Indigenous heritage can benefit our mental health and well-being.”

Vaenuku is one of many students inspired to participate in research because of the Burke collection. “When they can hold something in their hands that their ancestors made, it’s a deep visceral engagement,” Barker explains. “It’s holding history. It makes the idea of research immediate and relevant, and then their investment in the research is entirely different.”

Sven Haakanson, associate professor of anthropology and curator of Native American anthropology, also uses the Burke collection to inspire student research. In his ethnoarchaeology course, students learn how objects in the collection were made, from willow baskets to gut-skin kayaks to woven blankets. In class they process bear gut skin and learn to carve. For a final project they choose a piece from the Burke collection, research its history and materials, and recreate the piece using traditional techniques and materials.

Students have woven small textiles, making spindle whorls to process the raw wool, and have carved Lummi canoe paddles. One student created a traditional tortilla press based on an example in the collection. The student received guidance from her father, who had made a similar tortilla press for her mother. Haakanson encourages all students to seek out individuals with expertise.

“The students do amazing things for this project,” says Haakanson. “When they go to museums in the future, they will look at objects and think, ‘Wow, that must have taken a long time to make. I wonder who made it and what the context was.’ My hope is that, as a result of this experience, they think about the world around them in a more respectful way, realizing there’s more to it than just what you see.”

Christian Sidor also wants students to appreciate the effort behind every object on display. He believes that students who accompany him on collecting trips — including an annual summer trip to Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona — benefit tremendously from seeing all the steps involved from discovery of a fossil to its display in a museum. These steps include excavating the fossil, then painstakingly removing the rock encasing it (in the Burke’s vertebrate paleontology lab), studying the fossil, publishing findings, scanning and 3D printing the skeleton as an online resource, and finally displaying the fossil.

“Without a museum on campus, a lot of those links in the chain aren’t there,” says Sidor. “Students can look at fossils in books and peer-reviewed papers, but it’s not the same as seeing the fossil in your hands, seeing the complete life cycle of the fossil on display.”

Like Sidor, Adam Leaché, professor of biology and curator of herpetology and genetic resources, includes students on his collecting trips in locations around the globe. His focus is reptiles and amphibians, with specimens stored in glass bottles in 70% ethanol as part of the Burke’s herpetology collection.

Leaché became interested in herpetology through genetics research, finding that tremendous variations in traits among reptiles and amphibians provide insights into evolutionary biology. “Horned lizards are some of my favorites,” he says. “Some give live birth and others lay eggs. What factors lead to these variations within one genus of lizard? That‘s one of many interesting questions.”

Although Leaché has labs at the Burke and in the Life Sciences Building, undergraduates who join his research team always start by volunteering at Burke. “That gives them an appreciation of the diversity of reptiles and amphibians and how we catalog and care for them,” says Leaché. “They’ll volunteer at the Burke for up to a year before deciding on an independent research project.” Many of those student projects, using specimens from the museum collection, have led to published papers in peer-reviewed journals.

Asked about his roles as biology professor and Burke curator and whether he draws a line between the two, Leaché smiles.

“Where’s the line between my Burke Museum and Biology Department positions? There is no line,” he says. “It’s all for the same goals of doing research and building collections at the Burke and mentoring students and teaching. It’s all just one big mission.”

More Stories

Is This Presidential Campaign Different?

UW History professor Margaret O'Mara provides historical context for this moment in US presidential politics.

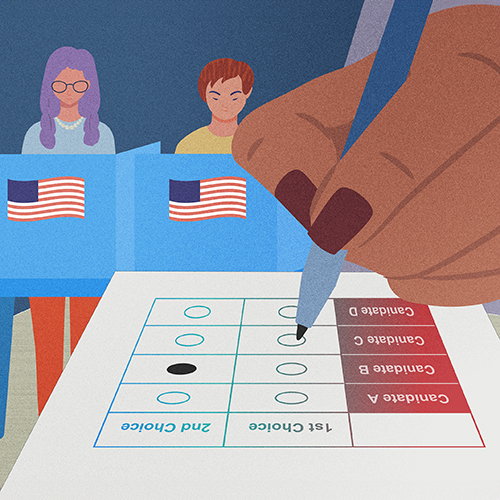

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

Making Sense of This Political Moment

To navigate this momentous election season, Arts & Sciences faculty suggest 10 books about the US political landscape.