The enduring works of Plato, Socrates, and other ancient thinkers — nearly all elite men — might suggest that ancient Greece and Rome were homogeneous places. A deeper dive into antiquity reveals tremendous diversity in the ancient world, with people from around the Mediterranean, from North Africans to Persians to Greeks, interacting regularly. But their conceptions of race and difference were quite different than ours in the 21st century.

“Our racial categories, particularly the fixation on skin color in terms of how we racialize other people, were not the categories that people in the ancient world used,” says Chris Waldo, assistant professor of Classics and co-chair of the Asian and Asian American Classical Caucus. “They conceived of difference and ‘foreignness’ in their own ways. And by looking at that earlier construction of race, we start to see the artificiality of our own present-day racial formation. It puts the arbitrariness of race as we know it into relief.”

Waldo explores this and related topics in “Race and Identity in Antiquity,” a new course he teaches in the UW Department of Classics.

Views about Difference

As an Asian American scholar in the predominantly white field of Classics, Waldo welcomes the opportunity to engage with students about race in antiquity. His own interest in Classics started in high school, with a class that compared democracies in 5th century BCE Athens, 1st century BCE Rome, and contemporary American democracy. “I remember learning about the Athenian invasion of Sicily at a time when the invasion of Iraq was building up,” Waldo says. “The parallels between the ancient world and the modern world seemed clear. Everything felt so present and relevant.”

Waldo hopes his course will similarly help his students see the relevancy of Classics. He starts by tracing Greek views about identity and difference back to the Persian invasion of Greece in the 480s BCE. Through hostile encounters such as the Battle of Marathon, Greeks faced people who seemed radically foreign, which led them to develop ideas about themselves and foreignness. Later, as the Roman Empire expanded and absorbed other cultures into its territory, those views became more complex.

They conceived of difference and ‘foreignness’ in their own ways. ...It puts the arbitrariness of race as we know it into relief.

A central belief was that a people’s geographic environment determined their traits — and their worth. People from temperate climates with abundant resources were seen as weak. Those from more harsh lands, such as the craggy and barren landscape of the Peloponnese — the heartland of ancient Greece — were seen as tougher, more resilient.

“This is a crucial way that Greeks and Romans are conceiving of difference,” says Waldo. ”They have a certain pride in their own ability to survive and flourish in this hard country, and they extrapolate from there.”

Complicating this theory was the belief that characteristics based on one’s geography would be passed down to future generations, even if they moved elsewhere. “It seems like you should have to choose one or the other, geography or genetics, but the ancients put those two things together,” says Waldo. “Then they start to conceive of notions about how a people’s biological qualities are fundamentally different and unalterable. That ends up informing eugenicists in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.”

The Past as Mirror

Aristotle, one of antiquity’s heavy hitters, famously argued that people are biologically determined to be masters or slaves. Some contemporaries disagreed, pointing out that former masters sometimes became slaves due to wartime capture, but Aristotle’s theories nevertheless gained traction. The Nazis and other eugenics movements over the past few centuries resurrected Aristotle’s argument to make their own case for some races being superior to others. Waldo covers this disturbing development, as well as other ways that the modern world has interacted with antiquity.

In fact, the second half of his course is devoted to looking at how people have engaged with the ancient world after antiquity. “Different groups of people definitely do latch onto different things,” says Waldo, who explores how specific groups — including Nazis, white supremacists, and contemporary Black, Latinx, and Asian American writers — reference the ancient world.

“The way I conceived of this class is that we spend the first half looking at ancient conceptions of race, and then we flip the mirror around and look at racialized people’s conceptions of the ancient world today,” says Waldo. “There are throughlines between the way that racialization worked in the ancient world and today.”

One example he introduces is The Island, a South African play in which two inmates in a South African prison stage a performance of Sophocles’ Antigone. “Antigone is about resisting authority and doing what you think is right morally even when the law does not conform to your conception of morality,” says Waldo. “In this play, the idea is picked up in the context of apartheid, where there is also an obvious distinction between the law and what a lot of people would consider morally right.”

While developing his course, Waldo was in touch with other Classics scholars planning similar courses. Colleges and universities across the country have started introducing courses on diversity in the ancient world, spurred by difficult conversations about race within the field of Classics and in the larger society. But, says Waldo, the UW Department of Classics is no newcomer to this topic. When it comes to addressing diversity in his field, the UW has long been a leader.

“I think an argument can be made that we’re the most progressive Classics department in North America,” says Waldo, who joined the faculty in 2020. He was particularly excited to come to the UW in part because of the Classics Department's proven commitment to diversity. “We have faculty whose work in gender and sexuality has been pioneering, and that permeates the culture of the department. My hiring has broadened that progressiveness to race because of who I am and the work that I do. A lot of departments are trying to catch up right now, but our department is at the forefront.”

More Stories

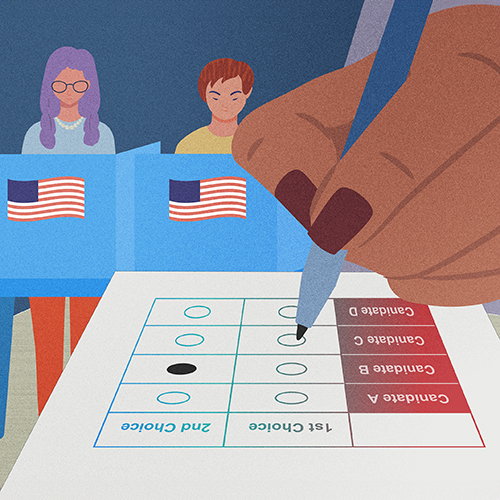

Democracy by the Numbers

Mathematics and Democracy, an undergraduate mathematics course, explores the role of math in many aspects of democracy, from elections to proportional representation.

Finding Family in Korea Through Language & Plants

Through her love of languages and plants — and some serendipity — UW junior Katie Ruesink connected with a Korean family while studying in Seoul.

Interrupting Privilege Starts with Listening

Personal stories are integral to Interrupting Privilege, a UW program that leans into difficult intergenerational discussions about race and privilege.