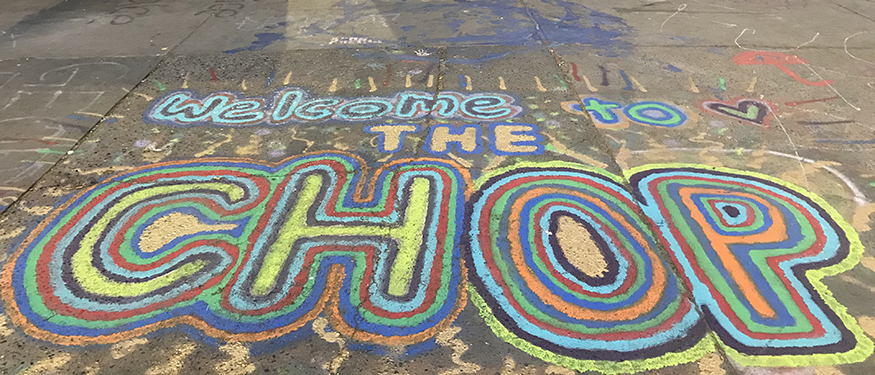

Nikki Yeboah recalls the moment the idea for her new play came to her. She was at brunch with friends in Seattle, enjoying mild weather and an elegant meal outside, when one of her companions mentioned that the 2020 Capitol Hill Occupied Protest (CHOP) — a month-long protest following the murder of George Floyd — took place in the same location. The disconnect was stunning to Yeboah, assistant professor of playwriting in the UW School of Drama.

“I was living in California at the time of the protests,” she says. “From where I was sitting in California, I felt like CHOP was a huge historical moment, so I assumed it would be something people in Seattle still talked about and that there would be vestiges from what happened. Instead, it felt like that moment in history had been completely sanitized. Doing the work I do, there was no way I was going to let this be forgotten.”

The work Yeboah refers to is documentary theater, or ethnodrama, which incorporates oral histories, media coverage, and other historical sources in the creation of a play about actual events.

An Emotional Retelling

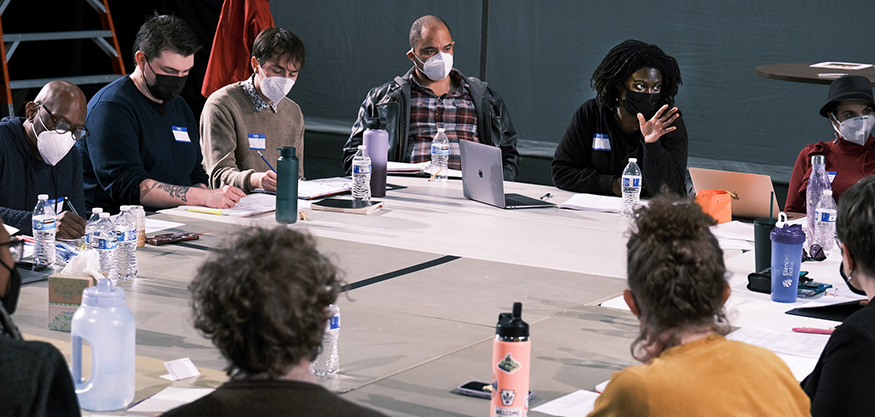

To write about CHOP, Yeboah first looked at published accounts of the protest: police reports, local and national newspaper and radio coverage, and social media posts. Then came interviews with nearly 30 CHOP participants and members of the surrounding community. She assembled an eight-member research team to help her, which included UW graduate and undergraduate students from drama, sociology, political science, communication, and other fields. The students spent last summer working on the project; they received small stipends thanks to the UW’s Black Opportunity Fund and Royalty Research Fund. Four students continued with the project during the academic year.

After protests, there are always questions, like ‘How did that move the needle on what protestors were fighting for? What could have been done differently? Who is accountable for how events unfolded?' This is a play that actually delves into that, like a postmortem.

“We gathered information from existing sources so we would know more about what happened before interviewing people.” Yeboah says. “It was also useful to get a sense of what names, events, and sites kept popping up. We eventually took ourselves on a tour of Capitol Hill, where each student chose a landmark and narrated why it was important to the movement.”

Next came interviews with those involved. Many of the interviews were emotional. Mona Merhi, a UW doctoral student in theatre history, recalls her first interview with a twenty-something CHOP participant. “In the middle of the interview, he couldn’t hold his tears while describing one of the violent scenes, where he witnessed the death of Lorenzo Anderson,” Merhi says. “This man experienced a lot of guilt because he could not do enough, he could not support enough. He kept repeating, ‘We were not ready.’”

Sam Sparkman, a UW senior majoring in communication, was particularly struck by the difference between the experience of those he interviewed and media accounts of the same events. “In the first months on the project, when we were strictly looking at media that already existed about the CHOP, it was easy to let the whole event become ‘past tense’ in my head,” Sparkman says. “But CHOP and the broader 2020 protests continue to impact countless people years after the fact. Interviews made that so obvious so quickly that it caught me off guard.”

Once the interviews were completed, Yeboah faced the daunting challenge of weaving those dozens of voices into a cohesive theater piece. She started by identifying themes and moments with emotional impact — moments that might create bridges between the CHOP participants and an audience watching the play. She then created composite characters and had them reunite years after the CHOP to make sense of what happened during the protests. She titled the play 11th & Pine, an intersection at the heart of the protest.

Ready for the Stage

With the first draft of the play completed, Yeboah held a private reading for those who’d been interviewed about their CHOP experience. Many had mentioned feeling misrepresented by the media, so Yeboah wanted to be sure that they felt heard in her work.

The reading did not go well. Participants felt Yeboah had leaned too heavily into media narratives about CHOP and hadn’t fully captured their experience. Yeboah realized she’d been trying to force the story into a neat narrative, when in reality, a leaderless movement like the CHOP has no neat narrative. There would never be a clear consensus about what happened.

“I changed about half the script after that,” Yeboah says. “It was very humbling, but very necessary. And the second table read went so much better. I was over the moon after that, because this time the group said, ‘Yes, you captured it.’”

Staged readings of 11th & Pine were presented by Sound Theatre Company in mid-March at Erickson Theatre Off Broadway, just blocks from the former CHOP site. Yeboah hopes there will be fully staged performances in the future in Seattle and beyond. She believes the play will resonate anywhere that protests have occurred.

“After protests, there are always questions, like ‘How did that move the needle on what protestors were fighting for? What could have been done differently? Who is accountable for how events unfolded?'" Yeboah says. “This is a play that actually delves into that, like a postmortem.”

For Merhi, who came to the UW from Lebanon in 2019 and witnessed her country’s unprecedented dissent movement from afar, one takeaway from this project is the commonalities in leaderless protest movements. “Whether we’re talking about Lebanon or Syria or Egypt or CHOP, there is always this feeling of Utopianism — the agora of the united crowd — that gets countered by infiltrations and by a late understanding of the leading protestors that they need time to build consensus and a common language,” Merhi says. “The similarities are astonishing.”

For Sparkman, the project demonstrated the profound impact that individual stories can have. He hopes that audiences gain greater empathy for protestors — as he has — thanks to the stories that CHOP participants shared.

“The unique opportunity we have in oral history is to take an event that is very easy to look at coldly and clinically at a societal level and make an audience engage with it intimately,” Sparkman says. “If a march was a thousand strong, that was a thousand people with lives and passions and fears who cared enough to put themselves in danger to overcome something terrible. That’s what I hope audiences take away — awareness and empathy for the people whose stories we’ve been lucky enough to help tell.”

More Stories

A Statistician Weighs in on AI

Statistics professor Zaid Harchaoui, working at the intersection of statistics and computing, explores what AI models do well, where they fall short, and why.

The Mystery of Sugar — in Cellular Processes

Nick Riley's chemistry research aims to understand cellular processes involving sugars, which could one day lead to advances in treating a range of diseases.

Interrupting Privilege Starts with Listening

Personal stories are integral to Interrupting Privilege, a UW program that leans into difficult intergenerational discussions about race and privilege.